ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

40 Great Spangled Fritillary Speyeria cybele (Fabricius, 1775)

The fritillaries are among our most beautiful, yet most vulnerable, butterflies. The stunning Great Spangled Fritillary is now our largest, after the extirpation of the Regal Fritillary. The Great Spangled is also our most successful greater fritillary; both the lovely Aphrodite Fritillary and the higher-elevation Atlantis Fritillary appear to be declining in the state, whereas the Great Spangled is holding its own.

The Great Spangled was probably common in Massachusetts a century ago, but that fact is obscured by some identification confusion with the Aphrodite Fritillary, which seems to have been more common a century ago than it is today.

Thaddeus W. Harris had five specimens in his Boston area collection, from 1820, 1823, and 1839; they are indexed as aphrodite (Index), but the specimens are labelled and appear to be cybele, which Harris seems to have thought was a variety of aphrodite. Harris does not list Great Spangled in his 1841 or 1862 books on Massachusetts butterflies, but does list Aphrodite. Scudder confirms that Harris’ published description does in fact apply to Aphrodite, but the indexing reflects some uncertainty (Harris 1862: 285-6, Fig 111; Scudder 1889:563).

Photo: Topsfield Mass., Ipswich River Wildlife Sanctuary, F. Goodwin, 2002

In 1862, in “A List of the Butterflies of New England” in the Proceedings of the Essex Institute, Scudder wrote of Argynnis Cybele “I do not know that this species is found in New England, but I have seen it from the Hudson River, and do not doubt it will be found in Connecticut.” By contrast, of Argynnis Aphrodite he wrote, “very abundant, about flowers, everywhere except in the most elevated and northern portions” of New England (1862: 165). This early impression of the abundance of Aphrodite may have been an over-estimate, since some collectors may have included Great Spangled Fritillary together with Aphrodite.

Scudder admits that Aphrodite and Great Spangled had been “frequently confounded” in New England (1899: 559), but by 1889 he himself was quite clear on the phenotypical differences between the two, providing detailed species descriptions of both, noting, for example, that “...the width of the submarginal buff belt is very different in the two species, forming indeed the readiest mark of distinction...” (1889: 566-7).

By 1899 Scudder has also changed his estimate of cybele’s distribution, saying that it was found probably throughout the whole of New England excepting the most northern and elevated parts, and was “exceedingly abundant” in southern New England, although he does not provide the usual list of specimen locations (1899: 559). By 1872 he had listed it as present in Essex County (1872).

Great Spangled Fritillary and Aphrodite Fritillary were both collected by F. H. Sprague in the Boston area in 1883. Of Sprague's many 1883 Malden, Wollaston and West Roxbury specimens in the MCZ and BU collections, 13 are Great Spangleds and 8 are Aphrodite. He also refers to a July 1, 1878, Wollaston specimen (Sprague 1879). In 1907, an unusual form of cybele was found flying in good numbers in West Roxbury, Massachusetts; again, no Aphrodites were reported from this location close to Boston’s urban core (Reiff 1910).

Out in the Connecticut River valley, Sprague captured even more specimens of both species, with Aphrodite Fritillaries sometimes outnumbering Great Spangled Fritillaries in this area. In the MCZ, there are 7 Aphrodite specimens from Belchertown and Leverett dating between 1878 and 1885, caught by Sprague, but only 3 Great Spangleds (including 2 extra-small ones from Mt. Tom, mentioned by Scudder 1899: 559). In his 1879 Psyche article, Sprague reports collecting 18 Great Spangleds and 16 Aphrodites in Belchertown and Leverett in 1878 alone. Finding so many Great Spangled Fritillaries in both eastern and western Massachusetts no doubt influenced Scudder's reassessment of this species' abundance.

By the mid-twentieth century, D. W. Farquhar (1934) published an updated assessment of New England’s butterflies. He lists new Great Spangled specimens from Boxford, Lawrence, New Lenox, Rehoboth, Marblehead, Stoneham, Essex, and West Roxbury (Reiff 1910), but only one probably erroneous specimen of Aphrodite; his list suggests that the Great Spangled had become fairly common in northeastern Massachusetts (Table 2), and that the Aphrodite was not common.

Other 1897-1918 specimens in the MCZ add the towns of Lexington, Wellesley, Weston and Tyngsboro. Howard L. Clark's 7/14/1914 Rehoboth specimen is also at Boston University, and 1933 specimens from Dover are at Yale.

The first records for Berkshire County seem to be C. W. Johnson's three 7/24/1917 specimens from New Lenox (presumably Lenox, since he also visited October Mountain and Mt. Greylock that day) at Boston University. Great Spangled Fritillary's presence in Berkshire County between 1950 and 1982, in Sheffield, Becket, October Mountain, Lenox, and Mt. Greylock, is amply documented in specimens in the Yale Peabody Museum. Yale specimens from Heath in 1982 document its presence in Franklin County, and specimens from Acton, Littleton and Boxborough in the 1960's (C. G. Oliver, Yale), and Westwood and Holliston in the 1960's and 1970's (Winter, MCZ) add additional eastern locations.

Great Spangled did not reach the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket to any great extent by the 1940's, or even today (see below). F. M. Jones was struck by the fact that while the Regal Fritillary was very common on both islands, its congener, the Great Spangled, "has been recorded only once from Nantucket, [and] has been seen in small numbers and at rare intervals on Martha's Vineyard, though it is reported to abound on Cape Cod" (Jones and Kimball 1943: 16). This despite an abundance of many species of violets on the islands. (A 7/23/1931 Martha's Vineyard specimen by F. M. Jones is at BU, a 21 July 1941 Jones specimen at Yale). Jones might have added that the Aphrodite Fritillary had also never been recorded for Nantucket, and only once for Martha's Vineyard. These two fritillaries had trouble establishing themselves in the dry, open island habitat, while the Regal Fritillary thrived.

Great Spangled Fritillary has the largest range of any of our eastern greater fritillaries. It extends as far north and west in Canada as the Aphrodite and most other fritillaries (Layberry 1998), but is also found much further southeastward, in the mountains and piedmont areas of Virginia, the Carolinas and north Georgia, and further south in the midwestern states (Opler and Krizek 1984; Cech 2005).

Host Plants and Habitat

All five species of resident fritillaries in New England—the Great Spangled, Aphrodite, Regal, Atlantis, Silver-bordered and Meadow --- undoubtedly benefited from the clearing of land for pastures, haying and timbering in the 17th and 18th centuries (Table 1: 1600-1850). Fields that are mowed or grazed, but not plowed, provide fertile areas for the spread of their larval host plants, violets of many species, and also increase nectar sources for adult butterflies. What has an adverse effect on fritillaries is tillage – the plowing of land in order to grow crops—because most species of violets (other than the Common Blue, which most of our fritillaries do not seem to use), are very slow to re-colonize disturbed areas, perhaps because they depend on ants for seed dispersal.

Viola fimbriatula (= ovata, sagittata) (arrow-leaf, northern downy), lanceolata (lance-leaved), sororia (=papilionacea, septentrionalis) (common blue), cucullata (blue marsh), rotundifolia (round-leaved), blanda (sweet white), and pedata (bird’s-foot) are among our most common native species, and all probably serve as hosts for Great Spangled Fritillaries (McGee and Ahles 1999; Sorrie and Somers 1999; Scott 1986). The larger fritillaries are known to accept several species of violet in lab rearings, but the precise species they use in the wild in our area has surprisingly not been determined. Shapiro (1974) reports a record of V. rotundifolia for New York state. MBC members have observed Great Spangled Fritillary ovipositing near Viola fimbriatula in Essex County. They have also found and raised larvae on the common blue violet found in many yards (e.g. D. Adams, 5/30/2011).

These and other violet species were common in the mid-19th century in Massachusetts; Thoreau’s 1850-60 journals, for example, make many references to violets and it appears they were abundant around Concord at the time. However recent research in Concord, based on Thoreau’s and other data, indicates that violets (Malpighiales) are among those flowering plant species whose flowering time does not respond quickly to climate change, and whose abundance is for that reason declining in Concord (Willis et al. 2008).

As habitat, Great Spangled Fritillary needs both open fields for nectar and partially shaded areas in open woods for larval growth on violets. Moist or dry deciduous woods with violets, as well as nearby meadows with nectar sources such as milkweed and thistle, are required. Great Spangleds will travel at least several kilometers in search of nectar however.

Fritillaries are not among the “Switchers” (Table 3); that is, most are not known to have adopted any new non-native host plants in the wild. Some fritillaries, including the Great Spangled, will oviposit on Viola odorata, which is naturalized from Europe, under confined laboratory conditions. But the Great Spangled Fritillary does not normally use the often extensive growths of this violet in disturbed yard or suburban situations.

Relative Abundance Today

The 1986-90 Massachusetts Atlas found Great Spangled Fritillary in 110 of 723 atlas blocks, and called it “common” in the state. By contrast, data from MBC records 2000-2007 rank the Great Spangled as “Uncommon-to-Common.” This species does not rank in the Common category: it is not as often seen as, for example, the Spring Azure, and it certainly is not Abundant (Table 5). In MBC data, the Aphrodite and Atlantis Fritillaries have been seen much less often than the Great Spangled, and both rank as Uncommon in MBC sight reports (Table 5).

One of the most dramatic findings of a recent list-length analysis of MBC 1992-2010 data was the statistically significant 23.9% increase in Great Spangled Fritillary in the state, in contrast to the 85.4% decline in Aphrodite Fritillary and 81.8% decline in Atlantis Fritillary (Breed et al. 2012).

Chart 40 gives a more detailed picture of yearly ebbs and flows, showing increases only after 2006. Sightings per trip were higher in 2007, 2008 and 2009 than in previous years, and this continued in 2010. Using this statistical measure, no marked upward or downward trend is evident overall 1992-2009; this is in sharp contrast to the decline seen in sightings per trip of Aphrodite Fritillary and Atlantis Fritillary .

Chart 40: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

Statistics published in the Massachusetts Butterflies season summaries also show the pattern of increases in recent years: the average number of Great Spangled Fritillaries seen on a trip was flat in 2007, up 113% in 2008, up 125% in 2009, and up 74% in 2010, compared to the average for preceding years back to 1994 (Nielsen 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011). By contrast, sightings of both Aphrodite and Atlantis show a decline in these years.

State Distribution and Locations

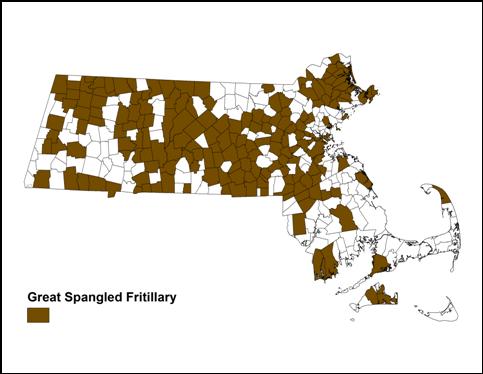

As Map 40 shows, the Great Spangled is well-distributed across the state, having been found in 176 of a possible 351 towns through 2009. Through 2013, it has been found in 189 towns. But it is much less common on Cape Cod and the Islands.

The 1986-90 Atlas did not find Great Spangled Fritillary on Cape Ann, Cape Cod or the Islands. However, MBC records now show sightings in all of these areas; notably, there are now many reports from Cape Ann, and a few from Martha's Vineyard.

Map 40: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1992-2009

On Martha’s Vineyard, the Great Spangled is a rare visitor today (Pelikan 2002), but it is the only fritillary other than the late-summer immigrant, Variegated Fritillary, to have been recorded on the Vineyard in the last twenty years. There are only three Vineyard sightings in 1992-2010 MBC records: Edgartown 7/29/1999, 1, S. Barry; West Tisbury, 9/17/2000, 1, V. Laux; and Oak Bluffs 7/31/2001, 1, M. Pelikan. The species has not been reported on the Martha’s Vineyard NABA Counts. Historically, this species was also "unaccountably rare" (Jones and Kimball 1943), with only a few reports: for example, at Vineyard Haven in July 1942, and two specimens from 21 and 25 July, 1941, F. M. Jones, in the Yale Peabody Museum.

There are no MBC or Atlas reports from Nantucket. There is one historical occurrence: C. P. Kimball reports one "seen in town but not captured" Sept. 8, 1941 (Jones and Kimball 1943).

Mello and Hanson (2004: 44) call the Great Spangled Fritillary “somewhat rare on the Cape.” This judgment is borne out in BOM-MBC 1992-2013 records, which show only two Cape Cod reports: Truro North, 8/7/1997, 1, T. Hansen; and Falmouth 7/11/1999, 2, A. Robb. Four Cape Cod NABA counts are held each year in July, but none since the 1999 Falmouth sightings has reported any Great Spangled Fritillaries. Great Spangleds are, however, quite commonly reported on the Bristol County NABA counts (25, 7/21/2002, and 7 on 7/21/2013, M. Mello et al.), and are often seen in the Westport/Dartmouth area.

Aside from the large numbers reported on many NABA Counts in July, there are some frequently-visited locations at which Great Spangled Fritillary may be reliably found in good numbers:

Charlton power line, 27 on 8/24/2011, B. Bowker, E. Barry; Harvard Fruitlands, 12 on 8/20/2008, M. Champagne; Hubbardston/Rutland Barre Falls Dam SP, 70 on 7/5/1999 M. Lynch and S. Carroll; Ipswich Appleton Farms TTOR, 25 on 8/4/2009 S. Stichter; New Marlborough, 25 on 7/11/2010, M. Lynch and S. Carroll; New Salem Prescott Peninsula, 63 on 7/10/1994 D. Small; Newbury Martin Burns WMA, 45 on 7/6/2008 S. Stichter et al.; Royalston, 53 on 7/15/1999 C. Kamp; Sharon Moose Hill Farm TTOR, 32 on 7/12/2009 E. Nielsen; Sherborn Brook St. power line, 23 on 7/3/2001 R. Hildreth; Sherborn power line, 13 on 8/22/2001 B. Bowker; Worcester Broad Meadow Brook WS, 40 on 7/22/2000 G. Howe; Williamsburg Graves Farm, 30 on 6/27/2010 B. Benner et al.

Broods and Flight Time

Great Spangled Fritillaries are apparently univoltine in Massachusetts, but they have a rather long flight time. Females emerge later than males. According to 1993-2008 MBC records, the flight period lasts from as early as the first week in June through as late as mid- October (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp). The butterfly is most common during the first three weeks of July.

Earliest sightings: In the 23 years of BOM-MBC records (1991-2013), the six earliest "first sightings" are 5/13/2012 Natick, G. Long; 6/1/2010 Ware, B. Klassanos; 6/6/1998 Charlemont, D. Potter; 6/7/2009 Grafton Dauphinais Park, D. Price; and 6/8/2013 Longmeadow Fannie Stebbins WS, schmev24 and 6/8/1999 Williamstown, P. Weatherbee. The very warm springs of 2010 and 2012 produced the earliest sightings.

Latest sightings: In the same 23 years, the six latest "last sightings" were 10/18/2002 Sherborn power line, R. Hildreth; 10/11/2013 Walpole, B. Sullivan (photo); 10/11/2009 Ware, B. Klassanos; 10/10/2006, Northampton community gardens, B. Spencer; 10/9/2011 Leicester, M. Rowden; and 10/8/1995 Newbury, S. Stichter.

Flight Advancement: A century ago Scudder wrote of Great Spangled Fritillary “the earliest butterflies appear in the latter part of June, sometimes as early as the 16th in the latitude of Boston, usually not much before the 21st, become common by the first of July when the female first emerges, ...and fly until the middle of September and occasionally later” (1889: 561).

Today, this species' flight time today begins earlier, and lasts longer, than it apparently did in Scudder's day. In nearly half (10) of the 23 years 1991-2013, the first fliers were seen in the first two weeks of June (6/1 through 6/14), rather than the latter part. Similarly, in about half (12) the years under review, the last sightings were well into October, rather than in mid-September. This change may be due to climate warming.

Outlook

All fritillaries are sensitive species, even though the Great Spangled may be the most successful and adaptable. Fritillaries are vulnerable to climate warming because all have fairly northerly ranges, and because their host plants, violets, do not re-colonize easily after soil disturbance and are also adversely affected by climate warming. However, Great Spangled Fritillary is not expected to be as negatively affected by climate warming in New England as Aphrodite and Atlantis Fritillaries.

Further habitat loss to intensive farming and to suburban development could reduce Great Spangled Fritillary numbers in Massachusetts. As NatureServe (2011) points out, the Great Spangled “does not use extensive violet populations in highly disturbed habitats, such as lawns or most city parks.” NatureServe advises that a viable “element occurrence” for any Speyeria fritillary will probably be at least 10 hectares, and that viable populations will need both wooded areas with violets and nearby open areas with adequate nectar sources. While Great Spangled Fritillaries will travel at least several kilometers, even across quite developed areas, to find nectar sources, they are not known as a wide-ranging species, and long flights may diminish reproductive success. So many medium-sized areas, with woods and open fields which are protected both from plow agriculture and from hardscape development, will be necessary to keep our Great Spangled populations flourishing.

© Sharon Stichter 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 1-4-2014

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS