ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

41 Aphrodite Fritillary Speyeria aphrodite (Fabricius, 1787)

The lovely Aphrodite Fritillary may be declining in Massachusetts today. It appears to have been more common in the 19th century in Massachusetts than it is now, despite some identification confusion with Great Spangled Fritillary. The earliest reports are from Thaddeus Harris, who called the Aphrodite “very common on flowers in low grounds in the latter part of July and the beginning of August” (Harris 1862: 286, Fig. 111). However, Harris' 1820, 1823, and 1839 Boston-area specimens, although indexed as aphrodite (Index), are labelled and appear to be in fact cybele, or Great Spangled, which Harris seems to have thought of as a variety of aphrodite.

Scudder in 1889, though acknowledging some identification confusion, still thought that Aphrodite Fritillary was "one of our commonest butterflies,” except where it was replaced at higher elevations (e.g. the White Mountains) by the Atlantis Fritillary. He reported that Aphrodites were "excessively fond of flowers and when feeding can be readily taken with the fingers. In July the sterile hillsides overgrown with thistles seem fairly alive with the butterflies. They frequent also low meadows and usually fly near the ground” – a flight pattern which indeed sounds more like Aphrodite than Great Spangled (1889: 568-9).

Photo: Royalston, Mass. Tully Dam F. Model, June 28, 2012

One of Scudder’s more famous passages reprints a poetic letter from a Colonel T. W. Higginson, writing from Princeton, Massachusetts, in the middle of July: “Often as I have dreamed of a more abundant world of insects than any ever seen, I never enjoyed it more vividly than in walking along the breezy, upland road, lined with a continuous row of milk weed blossoms and white flowering alder, all ablaze with butterflies. I might have picked off hundreds of aphrodites by hand, so absorbed were they in their pretty pursuit, and all the interspaces between their broader wings seemed filled with little skippers and pretty painted ladies and an occasional comma. The rare idalia and huntera sometimes visit them also, and a host of dipterous and hymenopterous things (Scudder 1889: 569).”

After a walk the next day along another road between the two Wachusetts, Higginson adds: “There was nothing of yesterday’s procession of milk weed and butterflies, though in the latter part of the way the aphrodites and tharos were so thick in the road, I brushed them away.” Scudder was aware that some observers of his day were confusing Great Spangled Fritillaries and Aphrodites, but he himself was clear about the distinction (see Great Spangled species account), and by choosing to quote Higginson’s letter gives a vote of confidence to this reporter’s identification skills. It is reasonable to conclude, as Leahy did in the Atlas account, that Scudder’s and Harris’ reports are correct, and that Aphrodite was fairly common in the late 19th century.

Both Aphrodite Fritillary and Great Spangled Fritillary were collected by F. H. Sprague in the Boston area in 1883, but Great Spangled seems to have been more common. Of Sprague's many 1883 Malden, Wollaston and West Roxbury specimens in the MCZ and BU collections, 8 are Aphrodite and 13 are Great Spangled Fritillaries. Judging from these numbers and Sprague's reported 1878 captures, Aphrodite was harder to find in the Boston area than Great Spangled. In 1878 Sprague found Aphrodites only in western Massachusetts, not in Wollaston (Sprague 1879). Similarly, in 1907 a local West Roxbury collector found cybele flying in good numbers in his area, but had not recently seen any Aphrodites there (Reiff 1910).

Sprague traveled west to the Connecticut River valley to collect even more specimens of both species, and Aphrodite seemed to at least equal Great Spangled in numbers in this area. In the MCZ, there are 7 Aphrodite specimens from Belchertown and Leverett dating between 1878 and 1885, but only 3 Great Spangled specimens (including 2 extra-small ones from Mt. Tom, mentioned by Scudder 1899: 559), all caught by Sprague. In his 1879 Psyche article, Sprague reports collecting 16 Aphrodites and 18 Great Spangleds in Belchertown and Leverett in 1878 alone. Other early (pre-1920) specimens at Boston University are from Princeton, Mass. (L. W. Swett, c. 1908); Harwich (c. 1912); Bristol R. I. (8/17/1914, H. L. Clark), and Mt. Greylock (7/21/1919, C. W. Johnson, a first for Berkshire County). At the MCZ can be found specimens from Lexington (C. Bullard, 7/17/1897) and Tyngsboro 1914 and 1919, H. C. Fall).

By the 1930’s, D. W. Farquhar published an updated assessment of New England’s butterflies. For Great Spangled Fritillary he lists nine new locations around Massachusetts, but for Aphrodite he lists no new locations, except for one "variant" from Essex, which he thinks was "probably an error" (Farquhar 1934). Farquhar's list thus suggests that whereas Great Spangled Fritillary had remained fairly common in Massachusetts by the 1930's, Aphrodite was less common. Similarly, the Gyspy Moth Lab in Dover caught 3 Great Spangled specimens in 1933, but no Aphrodite specimens (Yale). Aphrodite is therefore included on Table 2 as having decreased since 1900, although the reasons are not clear.

For the 1950-1980 period, there are far fewer museum specimens of Aphrodite than of Great Spangled Fritillary. However, Aphrodite's presence is documented in Franklin Co. (1952, "near Bear Mtn.", C. L. Remington); in Berkshire Co. again on Mt. Greylock (1954, R. Pease) and near Pittsfield (1960, D. S. Chambers); in Worcester Co. at Sturbridge (1977, C. C. Horton) and Barre (1972, Winter); and in the east in Acton (1957, 1965, C. G. Oliver) and Westwood (1969, Winter) (specimens at Yale and Harvard MCZ). Also in the east, Willis reported it from the Holliston-Sherborn-Framingham area in 1974 (LSSS Corresp. 1974).

In North America the Aphrodite and Great Spangled Fritillaries have largely overlapping ranges, both extending throughout Canada (Layberry 1998), but Great Spangled Fritillary today extends much further southeastward in the mountains and piedmont areas of Virginia, the Carolinas and north Georgia, and further south in the midwestern states (Cech 2005; Opler and Krizek 1984).

During the 20th century, the Aphrodite appears to have experienced range contraction along the southern edges of its distribution, not only in Massachusetts but also in the midwest and along the eastern seaboard. For Ohio, Iftner, Shuey and Calhoun wrote in the 1990’s that Aphrodite may have been more common in the past, with one 1930’s collector noting “the apparent decline of this species in southwestern Ohio during the early part of this century (1992:119).” Southwestern Ohio is at the southern limit of Aphrodite’s range.

After reviewing all historical records for New Jersey, Gochfeld and Burger concluded that Aphrodite was “probably rarer in the 1980s and 1990’s than in the 1950-1960 period, perhaps due to insecticide spraying,” and was “apparently declining in surrounding areas such as Westchester County, New York... (1997: 179; 33, Table 6).” They listed Aphrodite as exhibiting “a regional decline in the northeast.”

Host Plants and Habitat

All five species of resident fritillaries in New England—the Great Spangled, Aphrodite, Regal, Atlantis, Silver-bordered and Meadow --- undoubtedly benefited from the clearing of land for pastures, haying and timbering in the 17th and 18th centuries (Table 1: 1600-1850). Fields that are mowed or grazed, but not plowed, provide fertile areas for the spread of their host plants, violets of many species. What has an adverse effect on violets, and therefore fritillaries, is tillage – the plowing of land in order to grow crops. Most species of violets (other than the common blue, which our fritillaries do not seem to use much), are very slow to re-colonize disturbed areas, probably because they depend on ants for seed dispersal.

Viola fimbriatula (= ovata, sagittata) (arrow-leaf, northern downy), lanceolata (lance-leaved), sororia (=papilionacea, septentrionalis) (common blue), cucullata (blue marsh), rotundifolia (round-leaved), blanda (sweet white), and pedata (bird’s-foot) are among our most common native species, and all probably serve as hosts for fritillaries (McGee and Ahles 1999; Sorrie and Somers 1999; Scott 1986). The larger fritillaries are known to accept several species of violet in lab rearings, but the precise species they use in the wild in our area has surprisingly not been determined. Shapiro (1974) reports the use of V. fimbriatula, V. lanceolata, and V. primulifolia var. acuta (primrose-leaved) on Long Island in New York, and believes that use is confined to acid-soil violets.

All the violet species mentioned above were common in the mid-19th century in Massachusetts; Thoreau’s 1850-60 journals, for example, make many references to violets, which were apparently abundant around Concord at the time. However recent research in Concord, based on Thoreau’s and other data, indicates that violets (Malpighiales) are among those flowering plant species whose flowering time does not respond quickly to climate change, and whose abundance is for that reason declining in Concord (Willis et al. 2008).

As habitat, Aphrodite Fritillary needs both open fields for nectar and partially shaded areas in open woods for larval growth on violets. Dry deciduous woods with violets, and nearby meadows with nectar sources such as milkweed and thistle, are required. Shapiro (1974) reports poor or acid soil upland areas in New York. Opler and Krizek (1984) note that the Aphrodite is more habitat-restricted than the Great Spangled, being found in more acidic areas; they mention upland brushland, dry fields, and open oak woods, but also bogs, as the usual habitat.

Fritillaries are not among the “Switchers” (Table 3); that is, they are not known to have adopted any new non-native host plants in the wild. However, some fritillaries will oviposit on Viola odorata, which is the naturalized from Europe, under confined laboratory conditions.

Relative Abundance Today

Aphrodite has declined in abundance since Scudder’s day. Has anyone found “hundreds” at one spot in Massachusetts in recent years, as Col. Higginson did in the 1890’s? MBC records suggest that the Aphrodite cannot be described as “common” even in the central part of the state. Even the Atlas high count of 50 on July 9, 1979 in Millis (Norfolk County) could probably not be equaled today. Atlas author Chris Leahy noted in 1990 that “many experienced observers perceive a significant decline in this species in recent decades.”

The 1986-90 Atlas found the Aphrodite in 69 of 723 atlas blocks, making it “uncommon.” MBC sightings 2000-2007 also rank Aphrodite in the Uncommon category (Table 5). Great Spangled Fritillary is more often seen, and is in the Uncommon-to-Common category, while Atlantis Fritillary is even less often seen than the Aphrodite, and is ranked on the lower end of Uncommon.

One of the most dramatic findings of a recent analysis of MBC data 1992-2010, which used list-length as a proxy for effort, was the statistically significant 85.4% decline in Aphrodite Fritillary, and 81.8% decline in Atlantis Fritillary, in contrast to the 23.9% increase in Great Spangled Fritillary (Breed et al. 2012). Aphrodite Fritillary, Atlantis Fritillary, and Acadian Hairstreak were the three species with the greatest declines in detection probability over this period.

MBC sightings per total trip reports 1992-2009 also show a picture of serious decline for this species (Chart 41). 2010 continues the pattern of decline. There are no major changes in identification protocols, and no unusual reports of high concentrations at one location, to explain the higher numbers reported in earlier years. The pattern seems to be a slow but relatively steady decline, with a drop in 1995 and 1996, a bounce-back in 1999, but a return to decline thereafter. The high in 1999 is quite evident when looking at the reports from NABA Counts, particularly the Central Franklin, Northern Worcester and Northern Berkshire Counts.

Chart 41: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

Statistics published in the Massachusetts Butterflies season summaries show the same pattern of steady decline: the average number of Aphrodite Fritillaries seen on a trip was down 69% in 2007, 45% in 2008, 14% in 2009, and 8% in 2010, compared to the average for preceding years back to 1994 (Nielsen 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011). These figures contrast with increases in sightings of Great Spangled Fritillary for these years.

State Distribution and Locations

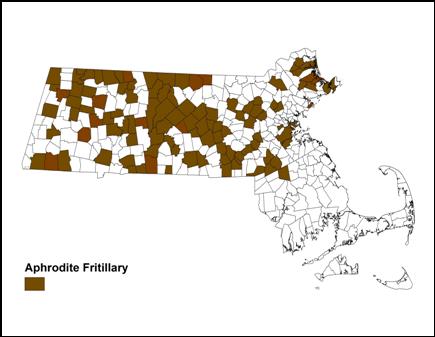

Map 41: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1991-2013

Aphrodite Fritillary was found in 105 towns between 1991 and 2013 (Map 41), compared to 189 towns for Great Spangled Fritillary.

Central Massachusetts stands out as the stronghold of Aphrodite Fritillary in the state (Map 41). This is most evident from Map 41 of BOM-MBC sightings, but can also be seen in the 1986-90 Atlas map. Perhaps this distribution was the case in Scudder’s day as well (recall Colonel Higginson in Princeton). Aphrodite is least common in eastern Massachusetts, in both Atlas and BOM-MBC records, and is absent from southeastern Massachusetts, Cape Cod, and the islands.

Neither the Atlas nor MBC has any reports of Aphrodite from the southeastern towns, from Cape Cod, or from the islands. There is one historical specimen from Martha’s Vineyard in the Yale Peabody Museum, collected by L. Cleveland on Aug. 29, 1936, but today, the Vineyard checklist terms Aphrodite “rare” or “accidental” (Pelikan 2002). There are no contemporary or historical reports from Nantucket (Jones and Kimball 1943; LoPresti 2011). Mello and Hansen (2004) do not mention Aphrodite as occurring on Cape Cod. The southernmost town for which MBC has records is Easton. The Atlas had records from the nearby towns of Attleboro and Norton.

Aphrodite is normally reported from each of the three Berkshire NABA Counts, but usually there are one or two years with larger numbers, while the rest of the years show only single digits, suggesting a decline over this period. For instance, the Northern Berkshire NABA Count reported highs of 24 on 7/15/1998 and 34 on 7/14/1999, but less than ten in every other year 1993 through 2013. The Southern Berkshire Count reported 40 in one year, 2002, but 8 or less in every other year between 1993 and 2013. The Central Berkshire count produced a high of 26 in 2001, but 20 or less, and usually 10 or less, in all other years 1991-2013.

The NABA counts with the most consistently high reports of Aphrodite are in central Massachusetts: Northern Worcester and Central Franklin. But all three central Massachusetts NABA Counts have shown declines in Aphrodite numbers since the 1990's.

The Northern Worcester Count found fairly high numbers through 2010 (between 23 and 34 reported in 1999, 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2010), but only between 2 and 8 were reported in 2011 through 2013. The long-running Central Franklin Count had a high of 52 reported in 1999, but has shown decline since: a similar number of observers reported 15 in 2009, 10 in 2010, 2 in 2011, 1 in 2012, but finally 26 in 2013. A striking decline is also seen in the Blackstone Valley Count numbers; this count reported 48 Aphrodites in 2001 (its first year), but never more than 9 between 2002 and 2009, and none 2010 through 2013.

There are several locations where Aphrodite was seen fairly consistently and in good numbers in earlier years, but for which there are no recent reports or visits. In Upton at the Chestnut Street Gas line, 42 were counted on 7/5/1999 by T. and C. Dodd, but the area has not been visited since 2000. In Newbury in northeastern Massachusetts, 25 were reported on 7/18/1993 by R. Forster, presumably from Martin Burns WMA, since that is the only area in Newbury known to be likely habitat. But recent reports from that state wildlife management area indicate a decline: 4 reported on 8/26/2000, F. Goodwin; 1 on 7/14/2001, D. Peacock; and none since, despite a thriving and much-counted colony of Great Spangled Fritillaries there. Other locations with large early reports but few to no recent reports are Princeton Wachusett Meadow Wildlife Sanctuary, 10 on 8/3/1992 T. Dodd; Savoy, 30 on 7/22/1994 D. Potter; Monroe, 11 on 7/19/1998 D. Potter; Petersham Quabbin Gate 40, 8 on 7/17/1999 D. Small; and Hardwick Quabbin Gate 45, 6 on 7/19/2003 M. Lynch and S. Carroll.

Aphrodite is present at Worcester MAS Broad Meadow Brook WS as of 6/30/2007 (G. Kessler, photo); at Holden Poutwater Pond (6/15/2013, B. deGraaf, photo), and at Williamsburg Flower Hill Farm (7/27/2013, C. Duke, photo). The site with the most consistent recent reports is Royalston Tully Dam, 5 on 8/3/2009 and Tully Lake, 5 on 7/13/2003 C. Kamp and D. Small. In Greenfield, 15 were counted on 7/6/2013, and 8 in Gill, by D. Small, S. Small, and L. Field.

COLLECTORS PLEASE NOTE: Because of the evidence of decline in this species, collectors are requested not to collect specimens except as part of necessary scientific research under the auspices of an educational or scientific institution.

Broods and Flight Time

Aphrodite Fritillaries are univoltine throughout their range, and do not have quite as long a flight time as Great Spangled Fritillaries. Males emerge several weeks earlier than females. According to MBC records, the flight in Massachusetts lasts from about mid-June through the second week in September (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp). Their flight begins later and ends earlier than that of Great Spangled. Like the Great Spangled, Aphrodite is most common during the first three weeks of July.

Earliest sightings: In the 23 years of BOM-MBC data (1991-2013), the six earliest "first sightings" are 6/9/2004 Mt. Greylock, T. Gagnon et al.; 6/10/2000 Hawley, M. Lynch and S. Carroll; 6/10/1998 Heath, D. Potter; 6/12/1999 Gill, D. Small et al.; 6/14/1991 Northboro, T. Dodd; and 6/15/2012, Holden Poutwater Pond, B. deGraaf (photo). Thus, in six of the 23 years, Aphrodite was seen in the first two weeks of June.

Latest sightings: In the same 23 years, the four latest "last sightings" were 10/2/1999, Royalston, C. Kamp, 9/28/2009 Northampton community garden, T. Gagnon et al.; 9/26/1998 Milford, R. Hildreth; and 9/24/1991 Milford, T. Dodd. The October sighting occurred in a year of particular abundance for Aphrodites (Chart 41). As sightings get fewer in later years, late flight dates are less common.

Flight advancement: Scudder wrote one hundred years ago that Aphrodite first appeared “about the first of July,” although a few might be found in the latter part of June (1899: 569). This timing for the first sightings is much later than today, when Aphrodite is fairly likely to be seen by June 15. Scudder also wrote that Aphrodite flies “until the middle of September,” which does not appear much different from today's experience. The location for these generalizations is not clear, but Scudder is usually referring to the latitude of Boston unless noted otherwise.

Outlook

The Aphrodite is declining in Massachusetts, according to MBC sight records. Whether this is a result of climate change, habitat loss, or other factors is uncertain, but climate warming is a likely cause (Table 6). Atlantis Fritillary is also declining, and Massachusetts has already lost one fritillary, the Regal Fritillary. As mentioned above, Aphrodite also appears to have declined in Ohio and New Jersey. It would appear that this species needs intensive monitoring, further study, and perhaps legal protection in this state.

Both Aphrodite Fritillary and Atlantis Fritillary have been designated here as Species of Conservation Concern .

As with Great Spangled Fritillary, further habitat loss to heavy farming and to suburban development could negatively affect Aphrodite Fritillary. As NatureServe (2011) points out, the the Great Spangled, and certainly the Aphrodite, avoid violet populations in highly disturbed habitats, such as lawns and most city parks. NatureServe advises that a viable “element occurrence” for any Speyeria fritillary will probably be at least 10 hectares, and that viable populations will need both wooded areas with violets and nearby open areas with adequate nectar sources. It is not known how far Aphrodite can comfortably travel to find nectar sources. Many medium-sized areas, with woods and open fields which are protected both from plow agriculture and from hardscape development, will likely be needed to retain populations of Aphrodite in the state.

© Sharon Stichter 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 1-5-2014

Species of Conservation Concern

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS