ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

43 Atlantis Fritillary Speyeria atlantis (W. H. Edwards, 1862)

Known in the 19th century as the Mountain Silver-spot, the beautiful Atlantis Fritillary was locally common in western Massachusetts in the early 1990’s; today it appears to be in woeful decline. Adapted to a northern climate and higher elevations, Atlantis is “trim and crisply marked” (Cech 2005), with a distinctive blue-gray eye.

Declines in both this species and Aphrodite Fritillary, and the extirpation of the Regal Fritillary, threaten to leave Massachusetts with only one fairly common larger fritillary, the Great Spangled Fritillary.

Photo: Mount Greylock, Mass. F. Model July 11, 2009

First described by W. H. Edwards in 1862, Atlantis Fritillary's original type locality was in the Catskill Mountains, at Hunter, Green Co., New York. (The type specimen and its label are in the Carnegie Museum; photos appear in Dunford 2005.)

In the late 19th century in Massachusetts, Atlantis Fritillary was known only from northern Berkshire County and possibly the Connecticut River valley. Thaddeus W. Harris had no specimens of Atlantis in his 1820-1850 Boston-area collection; only Aphrodite, Regal, and Great Spangled Fritillaries (Index). Prolific 19th century collector F. H. Sprague did not find it in eastern Massachusetts in the late 1800’s. In 1899 Scudder reports Massachusetts specimens from Easthampton (Mt. Tom), South Hadley, Leverett and Deerfield in "the valley," all said to be taken by F. H. Sprague, but there appear to be no supporting MCZ specimens for these towns. Scudder also reports Atlantis from Williamstown in Berkshire County (S. H. Scudder), where it was “not uncommon” (Scudder 1899: 576). By 1917, Atlantis had also been collected from Mt. Greylock and New Lenox (presumably October Mountain) in Berkshire County by C. W. Johnson (July 24 and 25, 1917, specimens at Boston University).

By the 1920's, Atlantis Fritillary ranged as far east as Essex County in northeastern Massachusetts; it was reported from Lynn, Essex and Stoneham (Farquhar 1934). Collector C. V. Blackburn found it in Stoneham, but said it was "very rare" there, and A. H. Clark found it in a field in Essex on July 9, 1925. His two specimens preserved at Boston University do indeed appear to be Atlantis Fritillary.

Between 1953 and 1983, Atlantis Fritillary was again well documented from Berkshire County, including Mt. Greylock (1954, R. W. Pease); Becket (1953, C. L. Remington, L. P. Brower); and October Mountain (1966, 1973, 1982, 1983, C. L. Remington, D. S. Dodge; 1973 S. A. Hessel); as well as in Franklin County from Heath (1981, 1982, S. D. Coe) (specimens at Yale and the MCZ). In western Franklin County, R. Wills Flowers collected it from Hawley Bog in 1966 (LSSS Corresp. 1966).

There appear to be no other reports or specimens from these pre-Atlas years from any other parts of the state, and specifically none from the Connecticut River valley. In 1986-90, the Massachusetts Audubon Atlas found Atlantis Fritillary well-distributed in twelve towns throughout Berkshire County (Mount Washington, Sheffield, West Stockbridge, Becket, Hancock, Otis, Washington (October Mtn.), Hinsdale, Florida, New Ashford (Mt. Greylock), Windsor and Williamstown), and in three towns in western Franklin County (Buckland, Monroe, Rowe), and two in western Hampshire and Hampden Counties (Plainfield, Tolland). None of these towns are in the Connecticut River valley, from which Scudder had perhaps mistakenly reported Atlantis in 1899.

Regionally, high elevation is the key to this species’ distribution. A century ago, Scudder reported it “abundant” in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (many Sprague specimens are in the MCZ), and it is still easily found there today (see photos on MBC website). In New York in the 1970’s, Shapiro (1974) reported it absent from “low, rolling country on the plateau,” but common in the Adirondacks and parts of the Catskills. Published maps (Cech 2005; Opler and Krizek 1984) show a disjunct between the eastern high-elevation New York/Pennsylvania/New England population, the western New York/Pennsylvania population, and the comparatively isolated population in West Virginia.

Host Plants and Habitat

Atlantis Fritillary is characteristically a boreal species. Its preferred habitat is high-elevation cold stream and river valleys, where it utilizes both meadows and forest openings. It also uses northern bogs. Scudder (1899: 376) reported that it preferred “sunny woodland nooks to open country.”

As with all fritillaries, the host plants are violets, although the precise species used in New England has not been determined. It may use several violet species. Shapiro (1974) reported it associated with V. septentrionalis (northern blue violet) in New York. Scott (1986) mentions V. adunca (sand-violet), V. nephrophylla (northern bog violet), and V. canadensis (Canada or tall white violet). All these are found in Massachusetts, but septentrionalis is the most widespread (Sorrie and Somers 1999), and may be the most likely host here.

The Atlantis probably benefited from the clearing of land for pastures, haying and timbering in the 17th and 18th centuries (Table 1: 1600-1850), particularly at higher altitudes. Fields that are mowed or grazed, but not plowed, provide fertile areas for the spread of violets of many species. What has an adverse effect on violets, and therefore on fritillaries, is tillage – the plowing of land in order to grow crops. Most species of violets are very slow to re-colonize disturbed areas, probably because they depend on ants for seed dispersal.

Violets are also among those species whose flowering time does not respond quickly to climate change, and whose abundance in our area may for that reason be declining (Willis et. al. 2008).

Like other fritillaries, Atlantis needs some open areas for nectar sources. A strong flier, it may travel quite far in search of nectar, but precise distances are unknown.

Relative Abundance and Trend Today

The 1986-90 Atlas found Atlantis Fritillary in only 20 out of 723 blocs, making it Uncommon. The published account called it “locally common,” but only a few spots in western Massachusetts would actually merit that description. MBC sight records 2000-2007 rank Atlantis on the lower end of Uncommon, from a statewide perspective (Table 5). It is less often seen than Aphrodite Fritillary.

Atlantis Fritillary has undergone a drastic decline in this state. A recent analysis of MBC data 1992-2010, using list-length as a proxy for effort, found a statistically significant 81.8% decline in Atlantis Fritillary, and 85.4% decline in Aphrodite Fritillary---compared to a 23.9% increase in Great Spangled Fritillary (Breed et al. 2012). Aphrodite Fritillary, Atlantis Fritillary, and Acadian Hairstreak were the three species with the greatest declines in detection probability over this period.

Additional evidence of Atlantis Fritillary's serious decline between 1992 and 2009 is shown in Chart 43, MBC 1992-2009 sightings adjusted by total trip reports. The main decline took place in the 1990's; since 2000 numbers seen per trip have been low but stable, and 2010, 2011, and 2012 continue the pattern.

Chart 43: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

Statistics published in Massachusetts Butterflies season summaries also show that numbers seen per trip have declined in recent years: 91% in 2007, 91% in 2008, 70% in 2009, and 74% in 2010, compared to the average for prior years back to 1994 (Neilsen 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011). Again, these contrast with increases for Great Spangled Fritillary.

The majority of reports of Atlantis Fritillary in the state come from the Central Berkshire and the Northern Berkshire NABA Counts. The results of these counts show the same sharp decline after 1999 as do the numbers for the state as a whole. Table 43 gives the raw numbers reported, and the numbers adjusted by party-hours of effort, from these two major Berkshire counts over the last 23 years. The counts produced high numbers of Atlantis in many though not all years up to 1999, then show a fall-off since. 1994 was a particularly productive year in both areas.

Table 43: Atlantis Fritillary reported on Central and Northern Berkshire NABA Counts 1991-2013

|

|

Central Berks. |

|

Northern Berks. |

|

|

Year |

No. Reported |

Effort-adjusted |

No. Reported |

Effort-adjusted |

|

1991 |

6 |

.29 |

|

|

|

1992 |

4 |

.11 |

|

|

|

1993 |

227 |

9.98 |

55 |

2.75 |

|

1994 |

630 |

30.00 |

230 |

10.45 |

|

1995 |

133 |

6.33 |

95 |

4.52 |

|

1996 |

77 |

3.67 |

2 |

.10 |

|

1997 |

102 |

4.21 |

36 |

1.13 |

|

1998 |

11 |

.48 |

64 |

1.87 |

|

1999 |

23 |

.74 |

156 |

5.47 |

|

2000 |

0* |

0 |

29 |

1.02 |

|

2001 |

0* |

0 |

2 |

.08 |

|

2002 |

5 |

.16 |

6 |

.15 |

|

2003 |

12 |

.43 |

count not held |

|

|

2004 |

2 |

.10 |

12 |

.74 |

|

2005 |

0 (heavy rain) |

0 |

16 |

.82 |

|

2006 |

12 |

.63 |

3 |

.12 |

|

2007 |

4 |

.12 |

0 |

0 |

|

2008 |

2 |

.11 |

1 |

.05 |

|

2009 |

9 |

.80 |

11 |

.49 |

|

2010 |

9 |

.5 |

count rained out |

|

| 2011 | 18 | .8 | 4 | na |

| 2012 | 3 | .2 | 5 | .14 |

| 2013 | 3 | .1 | 0* | 0 |

* The Count was held, and the two other greater fritillaries were reported.

The Northern Berkshire count began in 1993, and includes Mt. Greylock. The Central Berkshire count has been held since 1986, and includes October Mountain State Forest. The numbers of Atlantis seen in the 1980’s on the Central Berkshire count show that this species was also quite common in that area in those years: 1986 (60); 1987 (550); 1988 (70); and 1989 (366). (No Central Berkshire count data was reported for 1990. 1980’s data courtesy of G. Breed.)

State Distribution and Locations

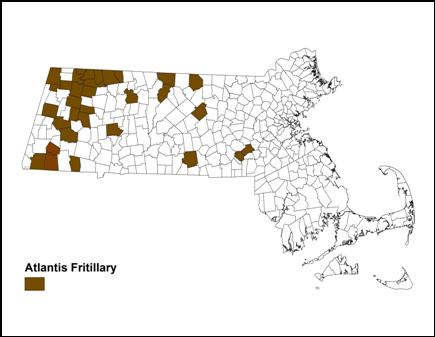

While central Massachusetts is the stronghold for Aphrodite Fritillary, the western and northwestern part of the state is the stronghold for Atlantis (Map 43). Atlantis was found in only 32 towns in BOM-MBC 1991-2013 records, compared to 105 for Aphrodite and 189 for Great Spangled Fritillary. (There are a total of 351 towns in the state.) Map 43 shades all towns where there has been even one report of an Atlantis Fritillary.

Map 43: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1991-2013

By far the most Atlantis Fritillary reports come from the Central and Northern Berkshire NABA counts; the Southern Berkshire and Central Franklin NABA Counts also frequently report Atlantis, but in fewer numbers. Atlantis is rare on the Northern Worcester and Blackstone Valley counts, and has never been reported from any counts further east. The 1986-90 Atlas did not find any Atlantis east of the Connecticut River valley. Map 43 shows the same, except for a few scattered reports.

Atlantis is a strong flier, and strays can sometimes be found far from expected habitat. Perhaps this is the explanation for those puzzling reports from Essex County in 1920’s, and for the few 1990’s reports in MBC records from the southeastern towns of Milford (1, 1999), Holliston (1, 1998) and Charlton (1, 1997). It should also be remembered that the potential for misidentification – confusion with Aphrodite or Great Spangled Fritillary-- is high. However, in the cases of Ashburnham and Athol, both near the New Hampshire border in Worcester County, central Massachusetts, specimens were taken in the mid-1990’s, confirming the reports for these two towns.

The following areas have had the highest counts of Atlantis Fritillary 1991-2013: Lee/Washington October Mountain State Forest , non-Count high 143 on 7/12/1998, but 18 on 7/16/2011, T. Gagnon et al.; Cummington, 30 on 7/3/1999 T. Gagnon, recent numbers lower; Florida, 45 on 7/13/1994 D. Potter; Hawley Dubuque SF, 7 on 7/3/2004, M. Lynch and S. Carroll; Savoy, 100 on 7/13/1994, D. Potter; Monroe, 20 on 7/19/1998 D. Potter; New Ashford Mt. Greylock, recent non-Count high 24 on 7/4/2005 S. and R. Cloutier; and Windsor Moran WMA, recent high 6 on 6/21/2002 M. Lynch and S. Carroll; Windsor Notchview TTOR, 8 on 7/10/2012 T. Gagnon et al.

COLLECTORS PLEASE NOTE: Because of the evidence of decline in this species, collectors are requested not to collect specimens except as part of necessary scientific research under the auspices of an educational or scientific institution.

Broods and Flight Time

Atlantis Fritillaries are univoltine throughout their range. Their typical flight time in Massachusetts appears to be shorter than that of the Aphrodite and Great Spangled Fritillaries, but MBC records may be missing the early and late parts of the flight, since they are based heavily on the NABA counts. According to 1993-2008 records, the flight in Massachusetts lasts from mid-June through July, with a few sightings in late August and mid-September (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp). Their flight begins later and ends earlier than that of Great Spangled. Like Great Spangled and Aphrodite, Atlantis is most common during July.

Earliest sightings: In the 23 years of BOM-MBC data (1991-2013) the six earliest "first sightings" of Atlantis Fritillary are 6/16/2004 Mt. Greylock, B. Benner; 6/17/2013 October Mountain, T. Gagnon; 6/17/2012 Windsor, T. Gagnon; 6/17/2009 Peru, B. Spencer; 6/18/2010 Cummington, B. Spencer; and 6/19/1998 Savoy, D. Potter. Four of these six mid-June first sightings have been in recent years -- 2009 - 2013. Particularly warm springs in 2010 and 2012 no doubt helped advance the flight date in those years. In another six of the 23 years, including many years in the 1990's, the first sightings were in the third week of June.

Latest sightings: In the same 23 years, the four latest "last sighting" dates are 9/20/1999 Milford power line, R. Hildreth; 9/12/1994 Heath, D. Potter; 9/1/2009 Savoy T. Gagnon and H. Allen; and 8/29/2004 October Mountain, B. Benner et al. Thus, in these years there are only three reports of Atlantis Fritillary flying into September.

For this species, the flight dates reported by Scudder are applicable only to the White Mountains in New Hampshire and the Catskills in New York, and therefore comparisons with Massachusetts are not possible.

Outlook

Several recent authors expect that climate warming in the northeast will lead to a decline in Atlantis Fritillary (O’Donnell et al., Connecticut Atlas, p. 292; Leahy, MAS 1986-90 Massachusetts Atlas; Cech 2005, quoting R. Dirig for New York; Breed et al., 2012). In Connecticut, Atlantis is state-listed as a species of special concern, and ranked S1 or highly vulnerable by NatureServe (2011). In this species, climate warming may cause withdrawal northward and movement to higher elevations. This and other species vulnerable to climate warming in Massachusetts are listed in Table 6.

In the last twenty years, both Atlantis Fritillary and Aphrodite Fritillary have declined sharply in Massachusetts. The state has already lost one greater fritillary, the Regal Fritillary. Atlantis Fritillary is therefore listed here as a Species of Conservation Concern. It needs increased monitoring, further study, and probably listing and legal protection.

As with the Great Spangled and Aphrodite fritillaries, habitat loss to resorts, golf courses, shopping malls, corporate headquarters and second homes could negatively affect Atlantis Fritillary. As NatureServe (2011) points out, Speyeria fritillaries do not make use of violet populations in highly disturbed habitats, such as lawns and most city parks. NatureServe advises that a viable “element occurrence” for any Speyeria fritillary will probably be at least 10 hectares, and that viable populations will need both wooded areas with violets and nearby open areas with adequate nectar sources.

© Sharon Stichter 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 1-5-2014

Species of Conservation Concern

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS