ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

95 Long Dash Polites mystic (W. H. Edwards, 1863)

A bright little meadow skipper, called Hesperia mystic by W. H. Edwards in 1863. The name mystic was also proposed by Scudder (1862), and was credited to him for many years before finally being assigned to Edwards (Miller and Brown 1981: 213, N128). Both Edwards and Scudder followed the convention begun by Harris of naming new skipper species in honor of Native Americans. The final defeat of the Pequot Indians took place in Mystic, Connecticut in 1636, and this may have been why both W. H. Edwards and Scudder chose the name (Zerlin 1995).

Scudder wrote that “In New England it occurs everywhere,” from the White Mountains and Maine to Cape Cod and New Haven. “There is hardly a local collection of any size which does not contain it....” It was less common in southern New England than northern, and “rather rarely found in the vicinity of Boston; nor have I taken it at Nantucket (1889: 1709).” He lists no specific locations, except Cape Cod. Perhaps its scarcity around Boston explains why Thaddeus Harris does not mention Long Dash or have it in his 1820-1850 collection. However, F. H. Sprague was able to take many specimens at Wollaston (Quincy) in 1878 --18 throughout June, and one on October 15 (Sprague 1879). About 1900, therefore, Long Dash appears to have been common, perhaps as common as Tawny-edged Skipper, but not as abundant as Peck’s Skipper or Least Skipper.

Photo: West Newbury, Mass. B. Zaremba, August 11, 2010

Like most meadow skippers, Long Dash probably increased in Massachusetts after 1600 as land was cleared for settlement and agriculture (Table 1). After about 1850, during the period of urban and industrial development, much meadow habitat was lost in the state, and Long Dash and other skippers may well have suffered some decline (Table 2).

The number of 19th century New England Long Dash specimens preserved in museums is small, and probably underestimates the true abundance. As with other skippers, Sprague found specimens not only at his home collecting base in Wollaston near Boston (1878, 1883, and 1885), but also in Malden (1885), Braintree (1895), out in Montague (1885), and in the White Mountains, N. H. (1889). Dr. J. S. Bailey found it in Albany, N. Y. (1876) (specimens in Harvard MCZ). There are early 20th century specimens from Tyngsboro (1918), Weston and West Newton (1920's) (MCZ), and Milton (Yale).

By the 1930’s Farquhar (1934) provides a fuller list of the many locations where Long Dash had been found. Farquhar apparently did not consider it as abundant as Peck’s Skipper or Tawny-edged Skipper, species for which he did not think it worthwhile to list the numerous locations and specimens. He knew of Long Dash specimens from Malden, Worcester (Forbes), Milton, Marblehead (F. H. Walker), Lynn, Stoneham (C.V. Blackburn), Wollaston (F. H. Sprague), Braintree (F. H. Sprague), Gilbertville (near Ware) (D. W. Farquhar), Phillipston (H. H. Shepard), Amherst (H. H. Shepard), and Nantucket (C. W. Johnson). In 1936 C. L. and P. S. Remington collected it at Hockamock Swamp in Taunton, and in 1938 in a cranberry bog near Ellisville in Plymouth County (Yale Peabody Museum). In 1942 V. Nabokov collected it in Wellesley (MCZ).

In the 1930's and 1940's, Long Dash was "general and common" on Nantucket and "widely present in suitable areas" on Martha's Vineyard (Jones and Kimball 1943). Four specimens are in the Kimball Collection at the Maria Mitchell Museum on Nantucket. There is one F. M. Jones specimen from Martha's Vineyard at the MCZ (no date). On Cape Cod, Long Dash was collected at Barnstable in 1952 (C. P. Kimball, MCZ), and at Brewster in 1961 (D. S. Chambers, Yale).

In the 1960’s Long Dash was first documented from Berkshire County: C. L. Remington collected it on October Mountain in Lee in 1965 (Yale Peabody Museum), and S. A. Hessel found it on October Mountain in 1966 (MCZ). Elsewhere, W. D. Winter found Long Dash in Westwood (1967,1972) and Dover (1973) in southeastern Massachusetts, as well as in Barre (1972 and Dunstable (1973) in north-central Massachusetts. J. M. Burns collected it in Dogtown, Gloucester, Essex County, in 1971 (MCZ). In the 1960's Long Dash was also extensively collected in Acton, Belmont and Littleton (1959-1966, C. G. Oliver, Yale), and though D. Willis does not mention it in his 1974 list of skippers occurring in the Holliston-Sherborn area, it seems likely to have been there (Lep. Soc. Seas. Sum and Corresp. 1959-1991). It seems to have remained fairly common.

Long Dash is a northern-based skipper. Along the east coast it is found southward only to mid-New Jersey, and inland it occurs only at higher elevations down to Virginia (Opler and Krizek 1994; BAMONA 2010; Cech 2005). It is found across the upper midwest and southern Canada to Washington state, and flies quite far north throughout Canada (Layberry et al 1998).

Like most northern butterflies, Long Dash is mainly single-brooded, but a partial second brood occurs near the southern edges of the range, such as Massachusetts (see below), probably Connecticut (O’Donnell et al. 2007), and possibly coastal New York and New Jersey (Scott 1986; Opler and Krizek 1984; but see Cech 2004). Shapiro (1974; 1966) reported a partial second brood for the coastal plain in New York, Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

Host Plants and Habitat

Poa spp. (bluegrasses) are the main hosts cited in the literature, but a question remains as to whether Long Dash uses the widespread Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis) in the wild. Confined females oviposit on it in the lab; the Connecticut Atlas raised Long Dash in the laboratory on Kentucky bluegrass, but did not report any field observations. Shapiro (1966) observed Long Dash ovipositing on Poa spp. in Pennsylvania, but the exact species of grass was not specified. Eggs are laid on or near the host plant, and larvae live in tied leaf shelters (Scott 1986). In Canada, Long Dash appears to have adopted several non-native grasses in addition to Poa (Layberry et al 1998), and thus is a candidate for possible inclusion in the list of Switchers (Table 3).

Kentucky bluegrass was introduced from Europe, and is now a common constituent of lawns and meadows across North America, flourishing in either wet or dry soil. However, it was also probably native in Canada and along the northern boundary of the United States (Gleason and Cronquist 1991). Thus its original range in North America may coincide with that of Long Dash, and it could have been the native host for this butterfly. If Long Dash is using mainly Kentucky bluegrass today, that would go far toward explaining the butterfly’s relative abundance. For Massachusetts, Sorrie and Somers (1999) do not list Kentucky bluegrass as originally native to any county, but as introduced in all of them. If that grass is the main host, then perhaps Long Dash moved into Massachusetts along with the importation of Kentucky bluegrass for pasture improvement in the 1700s. Or, Long Dash could have been, or could still be, using another Poa species here which is native, such as Poa palustris or fowl-meadow grass, which grows solely in wet meadows. Clearly, some research is needed.

Moist meadows and fields, marsh edges (including salt marsh edges), and streamsides are Long Dash habitat. The skipper can also found in grassy openings in forests or forest edges. It is an avid flower visitor, and even disturbed agricultural fields can provide nectar from red clover and cow vetch. In wet meadows, Long Dash is particularly fond of nectaring on blue flag (Iris versicolor), but also uses many other native and non-native nectar sources such as milkweeds and self-heal.

Relative Abundance Today

The Atlas found Long Dash in 118 of 723 blocs searched; this would rank it as “Common” (Table 5) and the Atlas termed it such. However, total reports of individuals in 2000-2007 MBC records rank Long Dash as “Uncommon-to-Common.” When compared to such truly common species as American Copper, Little Wood-Satyr, or Peck’s Skipper, it is simply not that frequently reported (Table 5).

Chart 95, showing numbers seen per total trip reports by year, suggests that there has been some decline in this species over the 1992-2009 period. Particularly good years for Long Dash, in relative terms, were 1992 and 2005, although 1992 is somewhat less comparable due to the smaller number of trip reports that year. The picture of decline rests partly on some especially large reports from 1992. But even if this is disregarded, the years 2007-2009 are still low in relation to the highs of 1995-1997 and 2005.

Separate list-length analysis of MBC data 1992-2010 yielded a similar result: a statistically significant 64.2% decline in detection probability of Long Dash over these years (Breed et al. 2012). In the Breed study, Long Dash was among a number of northerly-range species exhibiting declines in Massachusetts, attributed to climate warming.

Chart 95: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

For the years 2007-2009, statistics published in the Season Summary in Massachusetts Butterflies also chronicle relative decline. The average number of Long Dash skippers seen per visit to a location decreased 32% in 2007, 34% in 2008, and 16% in 2009 in comparison to the average for the preceding years back to 1994 (Nielsen, MB 2008, 2009, 2010). The number of reports also decreased in each year compared to the average for preceding years.

At least seven other well-known meadow skippers also show declines whatever statistical approach is used. Five declining dry meadow skippers are shown in Table A; wetland sedge-feeders such as Mulberry Wing and Black Dash are also showing declines.

State Distribution and Locations

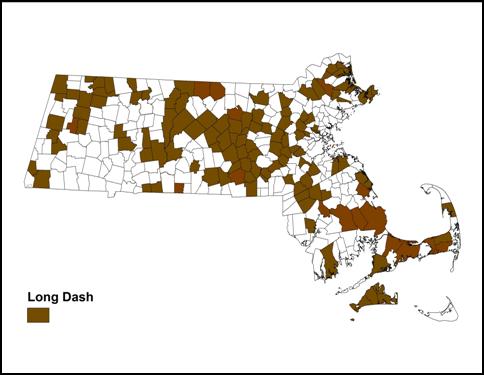

Map 95: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1992-2013

Long Dash is occurs throughout the state, and in this case BOM-MBC records largely confirm the distribution found during the 1986-90 Atlas. There are 1992-2013 records from 128 of the 351 towns in the Commonwealth (Map 95). In contrast, Peck's Skipper is reported from 206 towns in this period, Least Skipper from 150, and Tawny-edged Skipper from 153.

The Atlas had no reports from the lower Connecticut River valley. MBC records have filled that gap to some extent, with reports from East Longmeadow and Hampden, but surprisingly, there are still none from Longmeadow, Holyoke, South Hadley, Southampton, Springfield, or from many towns west of Springfield.

Long Dash is frequently reported on all three of the Berkshire NABA Counts, especially Northern Berkshire, based in Adams, from which it is reported most years in good numbers. It is also reported most years, in varying numbers (1-14) on the Central Berkshire Count, and in some years, in smaller numbers, from the Southern Berkshire Count. Among all the NABA Counts, the highest and most consistent numbers come from the Northern Worcester and the Central Franklin Counts. On the other hand, Long Dash has never been reported from the Lower Pioneer Valley Count, and only quite infrequently from the Bristol and Cape Cod Counts.

Long Dash has been found in some especially high numbers at specific locations in Essex County-- for example, Ipswich Ffolliott's Farm, 100 on 6/12/2005, S. Stichter et al.; Newbury William Forward WMA, 27 on 6/20/2005, S. Stichter; and Gloucester, 14 on 6/22/1995 D. Savich and C. Tibbits. These locations are not visited during the Northern Essex NABA Count.

Overall, Long Dash is somewhat harder to find in the southern parts of the state than the northern--- with the exception of Martha’s Vineyard. The Vineyard checklist lists Long Dash as Common (Pelikan 2002), and MBC has many reports, confirming Jones and Kimball's 1943 assessment. Surprisingly, MBC has no records from Nantucket, although there is one Atlas record and some historical specimens.

Interestingly, Long Dash has been found on many islands. The MAS Atlas had several records from the Elizabeth Islands (town: Gosnold) of Naushon, Nashawena, and Penikese. Mark Mello found Long Dash on Peddock’s Island in the Boston Harbor Islands on June 21, 2001, and there is a 2006 Harbor Islands specimen in the MCZ. . There are 1982 and 1983 specimens from Gosnold's Cuttyhunk Island (D. S. Dodge) at Yale.

Productive locations are generally open areas near wetlands. Notable reports include

Burlington Mary Cummings Park, 9 on 6/8/2011 B. Bowker; Carver Myles Standish, 10 on 6/27/2010 M. Arey; Edgartown SF, 20 on 6/27/2003 M. Pelikan; Falmouth Crane WMA, 10 on 6/30/2004 T Hansen et al; Grafton Dauphinais Park, 10 on 6/24/1998 D. Price; Groton Surrenden Farm, 5 on 6/10/2008, T. Murray; Hampden Laughing Brook WS, 7 on 6/12/1996, G. Howe; Hingham Turkey Hill TTOR, 10 on 6/1/2001 D. Peacock; Hinsdale, 4 on 6/18/2010, F. Model; Holden WTAG Towers, 6 on 6/5/2011 S. Stichter; Holliston Brentwood CA, 8 on 6/7/2009, B. Bowker; Hopedale Draper Park, 11 on 6/10/2002 B. Bowker; Hubbardston Barre Falls Dam, 24 on 6/19/1999 T Dodd; Lee October Mountain SF, 5 on 7/9/2004 B Benner and T Gagnon; Lenox George L. Darey WMA, 5 on 6/6/2009 E. Nielsen; New Ashford Mt Greylock, 6 on 7/10/2005 T. Gagnon et al.; Newbury Martin Burns WMA, 18 on 6/10/2012 S. and J. Stichter; Newburyport Little River Nature Trail, 12 on 5/28/2012, B. Zaremba, Maudslay SP, 15 on 5/28/2012, B. Zaremba; Orange,15 on 6/22/1997 D. Small; Paxton Moore SP, 5 on 6/10/2011 E. Barry; Petersham North Common Meadow, 15 on 6/20/2011 G. Breed and P. Severns; Princeton Wachusett Meadow WS, 10 on 6/19/1993 T. Dodd; Rockport Waring Field, 8 on 6/9/2001 F. Goodwin; Royalston Tully Dam 8 on 6/20/2012, R. and S. Cloutier; Tisbury Wakeman Center, 17 on 6/2/2002 M Pelikan; Topsfield Ipswich River WS, 11 on 6/11/2000 D. Marotte and W. Tatro; Uxbridge West Hill Dam, 19 on 6/15/1997 T. and C. Dodd; Wales Norcross WS, 29 on 6/21/2013 J. Ohop and E. Barry; West Newbury Cherry Hill Res., 10 on 6/10/2001 F. Goodwin; West Tisbury Nat's Farm, 22 on 6/4/2010 M. Pelikan; Westwood Hale Res., 12 on 6/9/2001 E. Nielsen; Williamsburg Graves Farm, 5 on 6/11/2005 B. Benner; Worcester Broad Meadow Brook WS, 13 on 6/5/2001 G. Howe.

Broods and Flight Period

According to the MBC 1993-2008 flight chart, Long Dash begins flying in mid-May, with good numbers by the last week of May and peak numbers in the second week in June (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp). Numbers drop off sharply by mid-July, but a few Long Dash continue to been seen through mid-September, the result of a partial second brood.

Earliest sightings: In the 23 years of BOM-MBC records 1991-2013, the seven earliest "first sightings" have been 5/7/2012 Royalston Tully Dam C. Kamp (unusually early; the next sighting that year was 5/17/2012 Barnstable Marstons Mills, J. Dwelly, still the earliest on record); 5/19/2004 Andover Ward Reservation TTOR, F. Goodwin; 5/22/1994 Granby T. Fowler; 5/22/1998 Worcester Broad Meadow Brook J. Mullin et al.; 5/22/1999 Clinton/Sterling, T. and C. Dodd; 5/25/2010 Holliston Brentwood CA, B. Bowker; 5/26/2007 Oxford Buffimville Dam, E. Baldwin.

In eleven (nearly half) of the 23 years from 1991 through 2013, the first Long Dash sightings have been in May. In an additional seven years, the first sighting was in the first week of June (6/1-6/7). The 1986-90 Atlas had reported that the first flight began in early June, with the extreme date June 1; today's dates are clearly earlier.

Comparison with Scudder’s nineteenth-century flight dates cannot be precise, because he gives Long Dash dates for only the southern and northern extremes of New England. But he says that in the extreme south of New England “the first butterflies make their appearance in the earliest days of June, perhaps even in May; fresh specimens continue to emerge during the first half of June, but by the middle of the month they begin to decrease and appear rubbed ... (1889: 1710).” Considering that this timing was meant to apply to southern Connecticut, it is striking how much earlier Long Dash is emerging today even at the latitude of Massachusetts.

Long Dash is normally single-brooded throughout its northerly range, with middle-instar caterpillars overwintering, but in some years, weather permitting, there is a partial second brood. That is, a portion of the mid-summer larvae do not enter diapause, but rather complete their development, producing small numbers of adults later in the season, usually August and September. Some sources (e.g. Opler 1984; Walton in MAS Atlas) have referred to this adaptive strategy as a full second brood, but the small size of the second flight indicates that it is partial here in Massachusetts (M. Arey, pers. comm. 8-22-2010).

Scudder was quite certain 100 years ago that there was a partial second brood in “southern New England,” saying that some of the Long Dash larvae produce a second brood of butterflies “the earliest of which appear from the 7th to the 10th of July (1899: 1710).

Latest sightings: In the same 23 years under review, the six latest "last sightings" were 9/30/2006 Dartmouth Allens Pond, E. Nielsen; 9/21/2005, West Tisbury, M. Pelikan; 9/20/2007 Rockport Waring Field, T. Whelan; 9/19/2013 Ipswich Appleton Farms, G. Kessler; 9/19/2008 Tisbury, M. Pelikan; and 9/17/2003 Northampton community gardens, T. Gagnon and T. Murray.

Scudder reported that second-brood Long Dash “continue on the wing until sometime into September.” Today's last sightings have been in September in 12 of the 23 years under review.

In over half (16) of the 23 years (1991-2013), there have been 1 or more sightings of adults later than August 15, Fresh individuals flying at this date or later are almost certainly part of the partial second brood. By this somewhat arbitrary measure nearly every year since 1998 could be called a ‘late brood’ year. In the late brood years there are at least 1 or 2 post-8/14 reports, nearly all of single individuals, some noted as fresh, with many of the late reports being from Martha’s Vineyard. The late brood years are 1995, 1996, 1998 (13 reports after 8/14), 1999, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013. The Atlas cites an 8/20/1986 report from Millis, B. Cassie, indicating that that may also have been a late brood year. Late brood years do not seem to coincide with high population years, but non-late brood years (1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1997, 2000 and 2009) partly coincide with population lows (Chart 95), however in those years observers may have just missed the late fliers.

In 2010 there was photographic field evidence of the partial second brood in Essex County. Mating was photographed on August 11 at Mill Pond Recreation Area, West Newbury by Bo Zaremba (photo above on this page), and fresh adults were photographed on August 20, 2010 at Appleton Farms in Ipswich by Howard Hoople. In 2011 there were post-August 15 reports from six locations, including Boxford, Lancaster, Belmont and Hingham. The latest report was 9/12/2011 in Hingham; a photo from Belmont on 9/11/2011 can be seen at http://www.flickr.com/photos/mcrainey/6181549649/in/photostream

Outlook

Given its northerly distribution and only partial second brood, this species could be adversely affected in Massachusetts by climate warming (Table 6). However, it is an uncommon-to-common species, and possibly adaptable as to host plant (research needed). Like many skippers, this species needs moist meadow habitats which are conserved and managed properly –that is, not mowed more than once a year. (See MBC Conservation page at http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/butterfly-conservation.asp ) Long Dash can probably not survive frequent, close mowing of its meadow habitats, turning them into manicured lawns, and not much is known about its ability to disperse and colonize new areas. Long Dash is still ranked by NatureServe (2010) as S5, or secure, in Massachusetts, but the recent downward trend and climate change are causes for concern.

© Sharon Stichter 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 8/19-2014

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS