ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

63 Northern Pearly-Eye Lethe [Enodia] anthedon A. H. Clark, 1936

A shy, crepuscular species, the Northern Pearly-Eye evokes New England’s woodland heritage. It is the region’s most forest-adapted butterfly. Its larval hosts are woodland grasses; adults feed on sap from tree wounds. Northern Pearly-Eye is usually found in the shady under-story, rather than the sunny canopy, and is often perched head-downward on tree trunks.

It was not until the mid-1930’s that the Southern Pearly-Eye (Lethe portlandia) was distinguished as a species separate from the Northern. [Use of Lethe rather than Enodia here follows Pelham 2008.] Until that time, both were known as The Pearly-Eye, and Scudder included them both in his discussion of Enodia portlandia in the 19th century. But the only species present in New England then, as now, was the Northern Pearly-Eye.

Photo: Ward Reservation, TTOR, Andover, Mass., Howard Hoople, 7- 2-2010

By 1862, Scudder had seen but a single specimen of this species, and by 1889 he wrote that “within the limits of New England it is very rare.” He cites the only known Massachusetts locations as the Notch near Holyoke (captures by Sprague and Scudder); Mt. Tom (numerous specimens by Emery); and Jamaica Plain, Boston (one specimen only) (1889: 184; 1862). A number of 1885 and 1886 Holyoke Range specimens by ardent collector F. H. Sprague are in the Harvard MCZ today. Thaddeus W Harris did not have a specimen in his 1820-1850 Boston area collection.

The obvious reason this forest-dwelling species was rare in the mid to late 19th century is that this was the period of maximum land clearance in New England, with perhaps half of all land in Massachusetts denuded of forests and devoted to active agriculture. Northern Pearly-Eye had probably declined since the pre-settlement period prior to 1600 (Table 1). But in the years subsequent to the agricultural era Northern Pearly-Eye has recouped its losses. It is not rare in Massachusetts today, merely uncommon.

Through the early twentieth-century Northern Pearly-Eye seemingly remained rare, with Farquhar in his regional review (1934) adding only the locations of Salem and possibly Stoneham to Scudder’s list. Specimens in the Harvard MCZ from 1914 and 1925 add Tyngsboro, further confirming the species’ presence in northeastern Massachusetts. But Northern Pearly-Eye was not present on the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket (Jones and Kimball 1943), nor is it found there today.

The late twentieth-century, in contrast, saw an outpouring of reports of Northern Pearly-Eye, and the species was probably expanding in numbers with the re-forestation of many formerly open areas (Table 2). In 1960 and 1966, collector C. G. Oliver found specimens in West Acton and Boxborough (Middlesex County) (Yale Peabody Museum). In 1967 collector R. Willis Flowers of Pittsfield found it at MAS Pleasant Valley Sanctuary in Lenox (Berkshire County), and at the other end of the state collector James P. Holmes of Essex captured a female at MAS Ipswich River Sanctuary in Topsfield (Essex County) (LSSS 1967). Holmes noted that the species “seems to be very local and scarce.”

In 1970, J. S. Ingraham collected Northern Pearly-Eye in Becket, in the Berkshires (Yale Peabody). In 1973 and 1974 Richard S. Robbins found Northern Pearly-Eye at Middlesex Fells Reservation in Medford/Stoneham. In 1975 he wrote to L. P. Grey that it was one of three species which “seemed to be particularly common, turning up in areas where they were previously uncollected” (LSSS and Correspondence, 1975).

In 1973 D. W. Winter collected a specimen in Westwood (Middlesex County) (Harvard MCZ). In 1975 P Carey "finally caught a Pearly Eye on July 27, on the Mount Holyoke Range along the forested Monadnock-Metacomet trail about one fifth of a mile west of Mount Norwottock” (LSSS 1975). In 1977 G. S. Morell took a specimen at Charlemont (Franklin County) (Yale Museum). In 1987, Mark Mello took a specimen at North Dartmouth (Bristol County) (LSSS 1987).

By the 1986-90 MAS Atlas period Northern Pearly-Eye was finally seen to be well-distributed across most of the state, except for southeastern Massachusetts and the Cape and Islands, where it was rare or absent.

Host Plants and Habitat

Moist, even wet, northern deciduous woodlands are the characteristic habitat of Northern Pearly-Eye, and while it is often found on dirt and gravel roads near forests, or basking on leaves along edges, it rarely ventures far into open meadows, since it does not nectar on flowers.

Like all woodland butterfly species, Northern Pearly-Eye imbibes tree sap; adults also forage on dung, carrion, rotting fruit, fungi and mud. A photo of a communal feeding on scat can be seen at http://www.flickr.com/photos/fsmodel/4420270207/in/set-72157623464167641/

Northern Pearly-Eyes are often more active at twilight than earlier in the day. Courtship takes place at dusk. Cloudy days are no deterrent to their flight. Northern Pearly-Eyes have even been found at moth trap lights at night: the only record for Cape Cod is an individual caught at a bait trap for moths (Mello and Hansen 2004: 52).

Based on MBC members’ field experience, Northern Pearly-Eye does not apparently require large unbroken tracts of forest; it can be found in small woodlands near housing developments (e.g. Lexington Great Meadows, Woburn Mary Cummings Park). Colonies are usually reported as “local” in the literature. The species is never observed flying long distances, but some dispersion must occur, since new areas seem effectively colonized.

Deer impacts on forests may be a concern, although NatureServe (3/2012) reports this species to be “holding its own” in deer-ravaged forests in New Jersey, as long as host grasses remain. Good patches of larval host grasses within the forest are necessary.

Larval host plants are a variety of woodland grasses. The 1995-99 Connecticut Atlas workers observed ovipositing on Orchard Grass (Dactylis glomerata) (O’Donnell et al., 2007). Shapiro (1974) lists Bearded Short-husk Grass (Brachyelytrum erectum) for Tomkins and Schuyler Cos. in New York. In Ohio, this species has been found and reared on Alta Fescue Grass (Festuca arundinacea) (Iftner et al. 1999). For other areas of eastern United States, many grass species have been recorded or suggested in the literature, including River Oats (Chasmanthium [Uniola] latifolia), Whitegrass (Leersia virginica), Bottle-brush Grass (Hystrix patula), and Plume Grass (Erianthus sp.) (Opler and Krizek 1984; Scott 1986). Eggs are laid singly on the host.

The precise grasses used in Massachusetts have not been determined. Orchard Grass (Dactylis glomerata) is a likely host in Massachusetts; it is introduced, but widespread. Leersia virginica and Hystrix patula [=Elymus hystrix] are also widespread here, and native. R. Walton, writing for the MAS Atlas, thought that Bottlebrush Grass (Hystrix patula), Wood Grass (Brachyelytrum erectum), and Purple Oats (Schizachne purpurascens) were the most likely food plants in Massachusetts. While the latter two are not very widespread in the state, the county distributions of these three grasses do correspond to that of Northern Pearly-Eye in the state (Magee and Ahles 1999; Sorrie and Somers 1999).

In New Jersey, Northern Pearly-Eye has apparently adopted the non-native invasive Japanese Stiltgrass (Microstegium) as a host plant, thus increasing its food security (Schweitzer, NatureServe 3/2012). Northern Pearly-Eye is not included in Table 3 “Switchers”, because it is not reliably known whether it has adopted non-native hosts in Massachusetts, but such adoption is likely.

Relative Abundance Today

Today (2000-2007) Northern Pearly-Eye ranks as Uncommon in Massachusetts, as measured by MBC sighting records (Table 5). The 1986-90 MAS Atlas had also labeled it as Uncommon.

MBC sightings per total trip reports (Chart 63) show a slight downward slide in sighting frequency over the years 1992-2009. Linear regression of the data in Chart 63 also shows a decline (R2 = 0.147). Peak flight period coincides with the NABA counts around the state, so there is no shortage of overall search effort over these years.

Chart 63: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

Analysis of MBC data by Dr. Greg Breed of Harvard Forest, using a different statistical approach, list length analysis, also shows this species to be slightly declining during these years, although not the steepest of decliners (Breed et. al., 2012). The decline is not easily explained, since forested habitat seems plentiful. Climate change may be a factor.

State Distribution and Locations

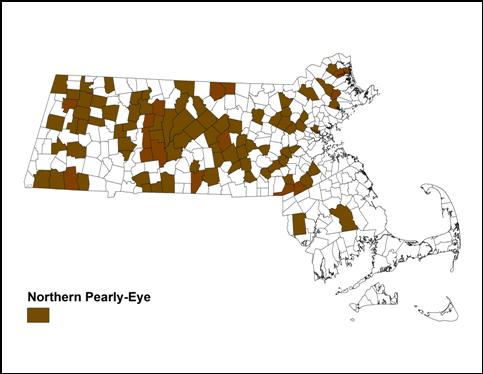

The 1986-90 MAS Atlas found Northern Pearly-Eye well distributed across the state, with the exception of southeastern Massachusetts and the islands, where it was rare or not found. BOM-MBC 1992-2013 data confirm this distribution (Map 63).

Map 63: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town 1992-2013

Northern Pearly-Eye was found in 93 out of 351 towns 1992- 2013 (Map 63). This is slightly fewer towns than Northern Cloudywing, for example, but more towns than Southern Cloudywing.

Southeastern Massachusetts: Middleboro and Rehoboth are the southernmost towns from which MBC has records. From Rehoboth (Bristol Co.) there is one report of a single individual in 2006, while from Middleboro (Plymouth Co.) the species was reported by K. Holmes on the NABA Count in 2001, 2002, and 2004, but not in subsequent years, and there has been no Count there since 2007. Previously, the 1986-90 MAS Atlas had no records from southeastern Massachusetts except for a 1987 report of a single in North Dartmouth by M. Mello. Northern Pearly-Eye has not subsequently been reported on any NABA Bristol County Count, though these have been held each year. Northern Pearly-Eye still seems quite uncommon in both Bristol and Plymouth Counties.

Cape Cod: For Cape Cod (Barnstable County), MBC has no reports, nor did the Atlas. Mello and Hansen (2004: 52).state that the only documented occurrence on Cape Cod is a specimen (no date given) captured by S. Smedley in a bait trap in the woods near Marstons Mills.

Islands: MBC records also confirm Northern Pearly-Eye’s absence from Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard. There are no Atlas or MBC records from these islands, nor any historical records (Jones and Kimball 1943; LoPresti 2011). Lack of suitable forest habitat likely explains the absence from the cape and islands.

Northern Pearly-Eye is not usually reported in large numbers from any one site, although since most are counted along trails in forests, there are probably many more at a site than are visible on a single hike-through. Significant single-site reports in MBC records are

Adams Greylock Glen, 5 on 8/5/2013, T. Armata; Belchertown Quabbin Park, 3 on 6/25/2010, R. and S. Cloutier; Burlington/Woburn Mary Cummings Park, 3 on 7/4/2007, E. Nielsen; Charlton Rt. 169 power line, 3 on 7/2/2001, R. Hildreth; Easthampton Mt. Tom, 13 on 7/26/1997, T. Gagnon; Hubbardston Barre Falls Dam, 10 on 7/12/1998, M. Lynch and S. Carroll; Lee October Mountain. SF, 13 on 7/10/1999, B. Cassie and T. Dodd; Monson/Wales Norcross WS, 6 on 6/28/2012, E. Barry et al.; New Marlborough , 11 on 7/3/1998, M. Lynch and S. Carroll; New Salem Prescott Peninsula, 6 on 7/11/1997, D. Small; Northampton Fitzgerald Lake, 4 on 6/29/2013, J. Rose et al.; Princeton Wachusett Meadow WS, 4 on 7/14/1996, T. Dodd and C. Asselin; Rutland Rutland SP, 4 on 7/3/2004, Barbara Walker; Savoy, 8 on 7/12/1995, D. Potter; Sharon Moose Hill Farm TTOR, 2 on 7/18/2009, E. Nielsen; Sheffield Bartholomew's Cobble TTOR, 3 on 7/17/1999, M. Lynch and S. Carroll; Ware Klassanos property, 4 on 7/4/2010, B. Klassanos; Royalston, 3 on 6/23/2000, C. Kamp; Westborough/Northborough Crane Swamp Trail, 3 on 7/27/2011, B.Volkle et al.; West Newbury Mill Pond RA, 3 on 7/11/2004, E. Nielsen; Windsor Notchview TTOR, 9 on 7/27/2011, T. Gagnon and F. Model.

Broods and Flight Period

Northern Pearly-Eye is not an obligate univoltine, like the Common Wood Nymph, but is normally single-brooded in New England climate. Only one brood is reported in Connecticut (O’Donnell et al. 2007) and New York (Shapiro 1974), but two further south, in West Virginia and Virginia (Allen 1997; Pavulaan 9/2010).

Four observations of fresh individuals flying in September and even October in Massachusetts show that there has been a partial second brood here in some years. The four second-brood observations are 1) two relatively fresh individuals 23 September 1987, Wilmington, S. Goldstein (LSSS 1987; MAS Atlas); 2) one individual 12 September 1994, Wellesley, R. Forster; 3) one individual 3 October 2007 Andover Ward Res. TTOR, H. Hoople (photo available); and 4) one individual, fresh, 7 September, 2014, Royalston, C. Kamp and A. Mayo. Pavulaan suggests that second brood emergence is temperature dependent and that more second-brood individuals will emerge in southern New England in years of especially hot, lengthy summers, reflecting the behavior of their southern congeners (9/2010 masslep).

Aside from these reports, Northern Pearly-Eye is most frequently seen flying from the last week in June through the first week in August, according to MBC 1993-2008 records: (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp)

Earliest sightings: In the 23 years of BOM-MBC records (1991-2013), the five earliest "first sightings" are 6/20/2004 Harvard Oxbow NWR, T. Murray; 6/22/2010 Wales, C. Kamp; 6/23/2000 Royalston, C. Kamp; 6/23/2001 Lexington Great Meadows, M. Rines (photo on MBC website); and 6/23/1991 Worcester Broad Meadow Brook WS, T. Dodd.

In 17 of the 23 years under review, the first sighting was in the third or fourth week of June (6/22-6/30), a remarkably consistent record. In very recent years, 2011 - 2013, the first sightings have also been in this time window: 6/26/2013, 6/28/2012, and 6/27/2011. In the remaining six years, the June fliers might have been missed, since the first sightings were in early July, often on the NABA Counts.

Latest sightings: Excluding two second-brood September-October reports, in the same 23 years the five latest "last sightings" are 8/23/2011 Grafton Dauphinais Park, D. Price; 8/22/1998 Northbridge Larkin RA, R. Hildreth; 8/21/1992 Tolland, T. Fowler; 8/21/2000 Northbridge Larkin RA, R. Hildreth; and 8/20/2009 East Longmeadow, K. Parker. Six of the 23 "last sightings" occurred in the third week of August (8/14-8/22).

Scudder’s reports of the flight dates for Northern Pearly-Eye in the 19th century were from Mr. Emery, who collected on Mt. Tom in Easthampton, Massachusetts. Emery found this species on Mt. Tom from “the last of June” to “the end of the first week in August (Scudder 1889: 185).” The spring flight week is the same as we see today. The most August sighting reports today are also in “the first week,” but today we also see quite a few still flying later into August, suggesting some lengthening of the “tail” of the flight period.

In 2011 egg-laying was observed on August 1 in Sandisfield, Mass. by M. Rowden.

Outlook

Northern Pearly-Eye is a northern-based species, but it ranges south in the Appalachian Mountains to north Georgia, and even further south in northern Alabama and Mississippi (Opler and Krizek 1984; Cech 2005). It does not occur at lower elevations along the southern seaboard; it is not found, for example, in southern New Jersey or coastal and piedmont areas of Georgia or the Carolinas. Northern Pearly-Eye could, therefore, be adversely affected by climate warming (Table 6). In Massachusetts, warming may be the most important threat to this species at this time.

However, this species has a wide geographical range, multiple broods further south, and uses a great variety of woodland grasses as host plants, even including at least one introduced, non-native grass (see above). All these factors argue for its general adaptability.

The re-growth of forests in Massachusetts in the last half-century, even on small tracts of land close to suburbs, highways and shopping malls, has been a boon for this species, allowing for its resurgence. The tendency of many conserved lands to revert to forest will continue to favor this species. This cannot be said for most other butterfly species, which require more costly, active management. For this reason, despite the rising temperatures from global warming, the outlook for Northern Pearly-Eye in this state is relatively good.

© Sharon Stichter, 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 9-10-2014

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS