ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

74 Northern Cloudywing Thorybes pylades (Scudder, 1870)

Thaddeus W. Harris at Harvard was the first to distinguish the Northern Cloudywing, but he called it a local variant of the Southern Cloudywing, T. bathyllus. Southern Cloudywing was well-known, as it had been figured by John Abbot and named by J. E. Smith in The Rarer Lepidopterous Insects of Georgia, published in 1797.

In the expanded 1862 edition of his report on injurious insects, Harris wrote “In Massachusetts we have what I suppose to be only a local variety of the Bathyllus skipper, differing from Southern specimens in the inferior size of the white spots on the fore wings, the less prominent hind angle of the hind wings, and the darker color of the fringes.” (1862: 312, Fig 135). Scudder then formally described Thorybes pylades as a species separate from bathyllus, noting that Harris’ figure exemplified his description (Scudder, 1872). Although the "type locality" is accepted as "Massachusetts" (Pelham 2008), Scudder's type specimen does not appear to be in the MCZ today.

Photo: Norwottuck rail trail, Amherst, Mass. F. Model 6-17-2005

The Northern Cloudywing “ has been found everywhere in New England in abundance from Nantucket and Connecticut in the south to the White Mountains and Maine in the north, in elevated stations as well as on the plains,…” wrote Scudder (1889: 1441). Northern Cloudywing had probably greatly increased as forests were cleared for agriculture after 1600 (Table 1). Similarly, Newton naturalist Charles Maynard (1886) described what he called the Dark-brown Tailed Skipper: “This is a very common species in Massachusetts, being found on flowers in June and July, and though a restless species, may be easily captured.” Maynard was referring to the Northern Cloudywing, because he says “this is the Bathyllus of Harris.” The Southern Cloudywing, on the other hand, was “not the bathyllus of Harris;” it was ”a rare skipper in Massachusetts only occurring, at least at all commonly, in the western portion of the state.”

Thaddeus Harris had ten local specimens of Northern Cloudywing in his Boston area collection; nine collected in 1826, one collected in 1833 at Mount Auburn in Cambridge (Index Lepidoptorum). Another early specimen in the Harvard MCZ is dated 6/13/1869, from Beverly, Mass., collected by Edward Burgess, Scudder's colleague at the Boston Society of Natural History; there is also one from Andover collected by F. G. Sanborn prior to 1884. F. H. Sprague collected a great many (at least 27 in the MCZ today) late 19th-century specimens of Northern Cloudywing. He found it in Wollaston (now Quincy) in 1878 (24 specimens collected there in 1878 alone), 1883, 1888, 1895 and 1896, at Milton Blue Hills in 1883, in Malden in 1883, 1885 and 1895, and also in the Connecticut River valley in Deerfield and South Hadley in 1885, Sunderland in 1886, and reportedly also in Belchertown in 1878 (Sprague 1879). (The South Hadley and Sunderland specimens were at first thought to be Southern Cloudywing, and may in fact be.) C. Bullard collected Northern Cloudywing in Waltham in 1897. In the early 20th century, C. A. Frost collected Northern Cloudywing in Stoneham and Framingham in 1903 and 1904, and C. W. Johnson collected it in Great Barrington in 1919, in what is probably the earliest Berkshire County record (specimens at BU). The MCZ has Tyngsboro specimens from 1918 and 1921, Stoughton specimens from 1929, Wellesley specimens from 1931 and 1942 (V. Nabokov), and a Lincoln specimen from 1937.

Donald Farquhar, in his 1934 review of New England lepidoptera, found Northern Cloudywing still “general and very common.” On Martha's Vineyard, pylades was "apparently rare" but there were specimens from 1931, 1937, and 1940 (Jones and Kimball 1943; 1 F. M. Jones specimen, n.d., BU). On Nantucket, it was "well distributed but rather infrequent" (Jones and Kimball 1943); there is one specimen from 1925 at Boston University and others in the Kimball Collection at the Maria Mitchell Museum on Nantucket.

In the mid-twentieth century, Northern Cloudywing was collected from many locations around eastern Massachusetts: Wellesley (1948, D. T. McCabe), Waltham (1949 and 1950, Gottschalk), Belmont, West Acton and Mt. Wachusett (1957-1966, C. G. Oliver) (all these specimens at Yale). W. D. Winter's Chelmsford, Millis and Westwood specimens (1971-74) are at the Harvard MCZ, species determined by J. M. Burns.

Host Plants and Habitat

The tick-trefoils (Desmodium) and the bush-clovers (Lespedeza) are key plant genera for several butterflies, including the Hoary Edge, the Eastern Tailed-blue, and the Southern and Northern Cloudywings. There are many species of these genera in Massachusetts: Sorrie and Somers list 12 tick-trefoils, all native to most counties, of which showy tick-trefoil or Desmodium canadense is probably the most common and widespread ( Magee and Ahles 1999), and 8 native bush-clovers. Round-headed ( L. capitata), hairy (L. hirta), and intermediate (L intermedia) bush-clovers are native to and found in all Massachusetts counties ( Magee and Ahles). Thus, the declining trend in abundance of Northern Cloudywings (see below) does not seem attributable to any lack of host plants.

Northern Cloudywing also uses another interesting native plant, hog peanut, (Amphicarpaea bracteata) which may not be abundant today, but is native to all counties in the state, and found in all but Plymouth County (Magee and Ahles 1999).

The Northern Cloudywing’s preferred habitats are dry open upland habitats, including old fields, power lines, and forest edges, but it can also be found in moister areas.

Northern Cloudywing has been adept at using introduced host plants (Table 3, Switchers). Red clover (Trifolium pratense) and alfalfa (Medicago sativa) are among its host plants (Scott 1986); White clover (Trifolium repens), birds foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) and introduced vetches (Vicia spp.) are also reported. The adoption of imported clovers is reported as far back as the 1880’s: Scudder wrote that “The caterpillar probably feeds on almost any of the Leguminosae, but its common food appears to be Trifolium and Lespedeza. The common red and white clovers, T. pratense and T. repens, seem to be most sought (1889: 1441).”

The 1995-99 Connecticut Atlas found Northern Cloudywing eggs or larvae in the wild on Desmodium and Lespedeza spp. and on introduced vetch (Vicia spp.). Northern Cloudywing has not recently been reported as using clovers as other than a nectar source in Massachusetts.

Relative Abundance Today

MBC sighting frequencies 2000-2007 rank both the Northern and Southern Cloudywings as “Uncommon” in comparison to common species (Table 5). The 1986-90 Atlas found it in 82 of the 723 blocs searched, making it more frequently found than the Southern Cloudywing, (20/723 blocs), but still “Uncommon” in overall rank. The Atlas characterized it as “common,” but this does not seem warranted, since it was nowhere near as common as the American Lady (171/723 blocs) or the Silver-spotted Skipper (160/723 blocs). Our benchmarks for the term “common” should be species that the casual observer might easily come across. But Northern Cloudywing is widespread, and can usually be found by the determined observer.

Chart 74: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

Chart 74a: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports 1992-2008

MBC sightings per total trip reports 1992-2009 indicate a decline in this species (Charts 74 and 74a). The charts show a strong downward trend, especially since a peak in 1997. This is the opposite pattern from Southern Cloudywing, which shows an upward trend (Chart 73). The same contrast between Northern and Southern Cloudywing trends was found in a separate analysis of MBC data which used list-length as a measure of detectibility; that study found a statistically significant 74.6% decline for Northern Cloudywing 1992-2010, compared to a 55.1% increase for Southern Cloudywing (Breed, Stichter, Crone 2012).

The high in 1997 is due to an unusual report of 56 in Mendon (6/8/1997, T. and C. Dodd), and the high in 1996 is mainly due to two reports a week apart of 26 each from Mendon (6/1/1996 and 6/8/1996, T. and C. Dodd.) These may have been localised population explosions. There are no other reports from single locations in the records which exceed 25, not even from NABA Counts. If these Mendon reports were halved, a trend downward would still be present, but it would be much less dramatic.

State Distribution and Locations

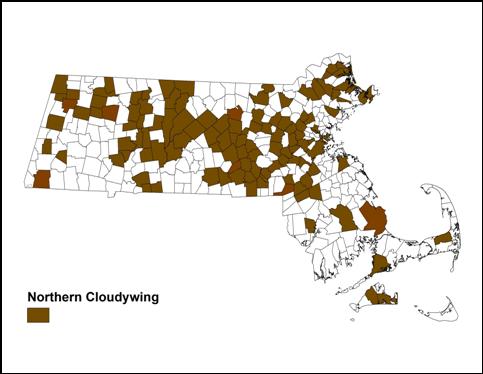

Map 74: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1991-2013

BOM-MBC records 1991 through 2013 show Northern Cloudywing in 117 towns across the state, as compared to only 67 for Southern Cloudywing. Northern Cloudywing is statewide, occurring in all counties west to east (Map 74), whereas Southern Cloudywing is mostly absent west of the Connecticut River valley. The distribution found by the 1986-90 MAS Atlas was broadly similar, but there are several notable changes.

The Atlas had found Northern Cloudywing uncommon to rare on Cape Cod and Cape Ann, and did not confirm it for Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, or large portions of southeastern Massachusetts.

Northern Cloudywing has now been quite thoroughly reported from Cape Ann by Doug Savich and Claudia Tibbits. These veteran butterfly watchers reported good numbers of Northern Cloudywings from Gloucester and Rockport every year from 1994 to 2005, a remarkable record. The high single-day counts were 19 in 2002 and 2003.

On Martha's Vineyard, the 1986-90 MAS Atlas did not find Northern Cloudywing, and Jones and Kimball (1943) had termed the species "apparently rare", but cited three specimens: 1931, 1937, and 1940. However, MBC now has many reports from West Tisbury and Edgartown, suggesting an increase in this species on the island since the 1930's. Local butterfly observer Matt Pelikan reported singles from West Tisbury and from Edgartown State Forest nearly every year from 1998 to 2003. Northern Cloudywing is listed as Uncommon on the Martha’s Vineyard checklist (Pelikan, 2002).

On Nantucket, Jones and Kimball (1943) had reported pylades as "well distributed but rather infrequent." The Atlas did not find it there, nor does BOM-MBC have any records. But there are historical specimens in the Maria Mitchell Museum, and observers feel that both Northern and Southern Cloudywings are likely candidates to be found on Nantucket (LoPresti 2011).

With regard to Cape Cod and lower southeastern Massachusetts, the Atlas finding of “uncommon” is largely corroborated by MBC records. Since 1990, neither Northern nor Southern Cloudywing has been frequently reported from these areas. The Falmouth NABA Count has not reported Northern Cloudywing since 1999, although it reported Southern Cloudywing from Crane WMA in 2005, 2006 and 2007. The other Cape NABA Counts (Truro, Barnstable and Brewster, all in existence since 2004) have produced only one report of 4 from the Brewster Count on 7/21/2007. Northern Cloudywing has never been reported from the Bristol NABA Count (located primarily in Dartmouth and New Bedford), although in 2004 that Count had one Southern Cloudywing. There are records of singles from the Dighton power line and Plymouth Myles Standish SF, and singles were found for several years on the Middleboro NABA Count.

The NABA Counts from which Northern Cloudywing is reported most frequently are Central Franklin (most years, max. 7 in 7/8/2006), Foxboro (most years in the 1990’s, max. 8 on 7/6/1997), and Northern Worcester (max. 7 on 7/6/2008).

Locations which have been productive for Northern Cloudywing include

Worcester Broad Meadow Brook WS, many reports, max. 25 on 6/4/2000 G Howe; Williamstown Mountain Meadow, max. 9 on 6/18/2011 B. Zaremba; Upton Chestnut St. gas line, max. 6 on 6/13/1999 T. and C. Dodd; Sharon Moose Hill Farm, 3 on 5/31/2010, E. Nielsen; Princeton Wachusett Meadow WS, max. 10 on 6/4/2011 C. Kamp et al.; Petersham North Common Meadow TTOR, max. 6 on 6/20/2011 G. Breed and P. Severns; Paxton Moore SP, 5 on 6/10/2011, E. Barry; North Andover Weir Hill TTOR, 3 on 6/15/2013, B. deGraaf; Newbury Martin Burns WMA, max. 9 on 6/16/2004 T. Whelan; Mansfield Maple Park, 6 on 6/14/2001 R. Hildreth; Leominster Doyle Reservation TTOR, max. 10 on 6/2/2010 R. Hopping; Hopedale Draper Park, max. 13 on 6/10/2002 B. Bowker; Hingham World's End TTOR, 7 on 5/12/2012, B. Bowker and L. Stilwell; Grafton Dauphinais Park, many reports, max. 21 on 6/10/2007 D Price et al.; Gloucester Industrial Park, max 10 on 6/5/1999 D. Savich and C. Tibbits; Falmouth Crane WMA, 3 on 6/11/2010, B. Cassie; Canton Great Blue Hill, 3 on 6/23/2012, S. Moore et al.; Boylston Tower Hill, 5 on 6/16/1999, B. Walker; Boston West Roxbury Millennium Park, 2 on 6/30/2010, B. Bowker; Athol Cass Meadows, 5 on 6/18/2006, C. Kamp et al.; Andover Ward Res., 4 on 6/19/2004, F. Goodwin; Adams Greylock Glen, 6 on 6/12/2004, P. Weatherbee; Acton Fort Pond Brook, 2 on 6/11/2007, J. Forbes.

Broods and Flight Period

According to MBC 1993-2008 records, Northern Cloudywing flies from mid-May to the first week in August (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp). This is slightly longer than the flight period for Southern Cloudywing. There is probably only a single brood, although the species should be watched for a partial second brood.

Earliest sightings: In the 23 years of BOM-MBC records 1991-2013, the five earliest "first sightings" are 4/15/2012 East Longmeadow, K. Parker [Note: this sighting is a full two weeks earlier than any previous report; a photo would have been desirable]; 5/1/2010 Barre Ware Riv., M. Lynch and S. Carroll; 5/10/1999 Cape Ann, D. Savich and C. Tibbits; 5/13/2001 Sunderland, T. Gagnon; and 5/16/2009 Groton, T. Murray. The effect of the particularly warm springs in 2010 and 2012 can be seen here.

Over the whole time period, four of the 23 years had first sightings prior to May 15, and another four years had first sightings between May 15 and 21. The remaining 15 first sightings were in the last week of May.

In the 19th century Scudder reported that this butterfly first appeared "toward the end of May, rarely earlier than the 24th and usually not until the 27th or later (1889: 1442-3).” The number of reports in the first, second and third weeks of May is more frequent today than Scudder's account would suggest. Such early flights are now more than just "rare." [Interestingly, F. H. Sprague first saw a Northern Cloudywing on the 7th of May 1878, in Wollaston (Sprague 1879), which may be the "rarity" to which Scudder was referring.]

Latest sightings: In the same 23 years of BOM-MBC records, the five latest "last sightings" are 8/5/2008 Sherborn Rocky Narrows TTOR, B. Bowker; 8/2/2004 Newbury Martin Burns WMA, S. and J. Stichter; 7/26/1997 Sterling, T. and C. Dodd; 7/25/2003 Middleboro, K. Holmes; and 7/25/2001 Worcester Broad Meadow Brook, G. Howe.

Over the 23 years there are two last sightings in August, seven in the last week in July, and five in the third week in July (7/14-21). But in the five years 2009-2013, the last sightings have been earlier (mostly on NABA Counts, which is where the main effort has gone).

Taken as a whole, these late dates are later than those suggested by Scudder, who said that “a few always linger on until at least the middle of July and in elevated districts until the end of July" (1889: 1442-3). The two August sightings may indicate a partial second brood, as Scudder believed, but probably simply reflect a longer flight period.

About broods, Scudder wrote “...the second brood of butterflies, which is much less abundant than the first (probably because many chrysalids continue until the next spring), appears in August, perhaps sometimes as early as the beginning, but usually not before the middle of the month, continuing upon the wing until past the middle of September; whether the progeny of this brood reaches the chrysalis stage before winter approaches has never yet been determined; if not it probably perishes (1889:1443).”

Why Scudder reported an August brood for Massachusetts is unclear, since all museum specimens cited here are from late May, June or early July. In recent times, Mello and Hansen (2004) have suggested a partial second brood for Cape Cod, and Layberry (1998) reports a partial second generation in August in extreme southwestern Ontario. But the 1995-99 Connecticut Atlas reports “one generation, late May to early July” (O’Donnell et al. 2005). The evidence from BOM-MBC records, only two August sightings in 23 years (whether "last" or not), does not strongly suggest a second brood. It is more likely that, as this species declines in numbers here, a second brood, even partial, becomes quite rare.

Outlook

The apparent decline in Northern Cloudywing is not easy to explain. Northern and Southern Cloudywings are sympatric over much of their continental range, with T. pylades having a wider, more northerly range (well into Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont), and being found more often in woodlands and higher elevations, but coexisting with T. bathyllus in many areas. It does not seem likely that an increase in populations of Southern would pose competitive pressures for the Northern. The Northern’s range also extends well southward, where it has 2-3 broods, so that climate warming does not seem a factor that would produce decline.

Climate warming here would increase the likelihood of a partial second brood, and observers should be on the alert for this possibility. Population trends in both Northern and Southern Cloudywings in Massachusetts need better monitoring.

Cech and Tudor (2005) classify Northern Cloudywing as an adaptable “generalist” species. The Connecticut Atlas found no change in the status of this species. Its NatureServe (2010) rank in Massachusetts is S5, or secure.

© Sharon Stichter 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 9-30-2014

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS