ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

31 Hesselís Hairstreak Callophrys hesseli Rawson & Ziegler, 1950

Closely related to the Juniper Hairstreak, Hesselís Hairstreak was defined as a separate species in 1950, on the basis of observations made by Sidney Hessel, an accomplished amateur lepidopterist from Connecticut. These two greenish hairstreaks look superficially similar, but have several distinguishing field marks; they also differ in habitat, host plant, and number of broods. Hesselís Hairstreak is found only in white cedar swamps, where its host tree, Atlantic white cedar, occurs, and has only one brood in most of New England. In Massachusetts it is state-listed as a species of Special Concern, because of its dependence on a specialized and declining habitat.

Photo: Ponkapoag Bog, Randolph, B. Spencer, May 29, 2007

History

Hesselís Hairstreakís status in Massachusetts before 1950 is unknown, because the species was not distinguished from Juniper Hairstreak. It has been reported that a 1941 specimen from Milton was subsequently identified as Hesselís (MAS Atlas), but the location of that specimen today is unknown; it does not appear to be in the Harvard MCZ.

Hesselís Hairstreak probably populated many of the numerous white cedar swamps in pre-settlement Massachusetts. After agricultural settlement, the draining of many wetlands for farming, and then for cranberry bogs in southeastern Massachusetts, plus the voracious demand of early settlers for wood of any kind, and the export market for wood, all led to the loss of many Atlantic white cedar swamps by 1900, and undoubtedly an associated decline in Hesselís Hairstreak (Table 1).

In the pre-industrial era both rot-resistant cedars, red and white, were in demand for fence posts, although the more common red cedar was favored for this purpose. White cedar was straight-grained and insect-resistant, and particularly valued for siding and roof shingles. Atlantic white cedar was also widely used for boats, barrels, buckets, decoys, utility poles, and railroad ties. White cedar grows in swampy areas in closely spaced clumps, so that one-time clear-cutting was the usual method of harvest.

After Hesselís Hairstreak was identified in 1950 on the basis of studies in New Jersey, the first Massachusetts report of this butterfly came in 1972, when Roger W. Pease wrote to the LepidopteristsĒ Society: ďI took 4 males of C. hesseli in the Wilbraham white cedar bog on May 29, 1972. Wilbraham is located immediately east of Springfield MassĒ (LSSS Correspondence 1972). Pease later reported that his specimens were deposited at the Yale Peabody Museum (Massachusetts Butterflies 25, Fall 2005). However, a search of the museum's on-line catalog, and an examination by the curator of the pinned specimen trays, does not turn up any Wilbraham specimens (L. Brown, pers. comm, 5-23-2011). Thus this 1972 report -- the only one known from the Connecticut River valley Ė still needs specimen or photographic confirmation. In 2011 and 2012, local amateur groups attempted to locate the species at the purported Wilbraham site, but without success.

Hesselís Hairstreakís presence in the state was conclusively established in 1980; numerous specimens by William D. Winter from 24, 25 and 31 May of that year, from a bog in Westwood, are in the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology (see also LSSS 1980). Specimens from 26 May, 1981 from a power line cut on the Dover-Dedham line, by Larry Gall, are in the Yale Peabody Museum. In Darryl Willis' collection is a specimen from 10 May, 1984, from a swamp in Hopkinton which is now lost to development. An 11 May, 1985 specimen from Ponkapoag Bog in Milton by R. Webster, and several 25 May, 1986 specimens from Westwood by R. Godefroi, are deposited at the McGuire Center in Florida.

Host Plants and Habitat

Hesselís Hairstreak is found only in Atlantic white cedar swamps and bogs, where its host tree, Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides) is the dominant plant. Atlantic white cedar is native to and found in all Massachusetts counties except Berkshire, Franklin, and Hampshire counties (Sorrie and Somers 1999).

Atlantic white cedar is the sole natural host of this specialized hairstreak, although red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), the host for Juniper Hairstreak, has been accepted in the laboratory (Opler and Krizek 1984).

Eggs are laid on the branch tips of Atlantic white cedar. The larvae feed on new leaf growth for about a month, and pupate in July. The pupae remain in diapause until the following May, probably under loose bark on the trunk of the host plant (NHESP 2007). Timing of emergence in May can be delayed by cold maritime springs.

Hesselís Hairstreak also needs nectar sources, which are sometimes scarce within treed swamps, and so the butterfly will travel some distance in search of nectar, into nearby fields, yards and roadsides. The most common nectar sources used within white cedar swamps in the north are highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) and chokeberry (Aronia spp.). Observations by Mike Nelson, NHESP, have confirmed the use of Aronia, of which there are three Massachusetts species. Hessel's Hairstreak uses primarily red chokeberry (A. arbutifolia) and the more common purple chokeberry (A. x floribunda = A. x prunifolia), both of which prefer wet soils. Black chokeberry (A. melanocarpa) prefers drier soils and thus is less used by this butterfly (M. Nelson, pers. comm. 11/9/2012). Other possible sources in Massachusetts are buttercups (Forster), and leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata) (Rainey).

Today, Atlantic white cedar swamps, and the Atlantic white cedar bogs which often occur within them, are NHESP Priority Natural Communities in Massachusetts These communities require natural alternation of wet and dry hydrological cycles, and ironically, regenerate best after catastrophic disturbance such as hurricanes and fires, since piecemeal selective cutting appears to favor red maple, which will out-compete and and replace the Atlantic white cedar (NHESP Fact Sheet 2007).

Based on experience in New Jersey, it appears that Hesselís Hairstreak is an effective colonizer, and can utilize trees of any age. Thus, restoration of white cedar swamps, and the replanting of white cedar stands, is an important and viable option to increase habitat for this species (NatureServe 2012; Schweitzer et al. 2011).

Relative Abundance Today

Although the 1986-90 MAS Atlas had ranked Hesselís Hairstreak as Rare in the state, the number of MBC sightings in 2000-2007 rank it as Uncommon-to-Rare relative to other species in the state in these years (Table 5). It does not appear to be as rare as Bog Elfin, Persius Duskywing, Common Roadside-Skipper, or Gray Comma.

Chart 31: BOM-MBC Sightings by Year, 1992-2013

Hesselís Hairstreak was seen or photographed in 11 of the 22 years from 1992 through 2013 (Chart 31). There were no field trips or searches made in 2009, 2010, or 2011, and thus no reports, but in 2012 Hesselís Hairstreak was photographed again at Ponkapoag Bog in Canton by M. Rainey on May 20, 2012, with a report of 3, possibly 5, individuals (photo in Massachusetts Butterflies 39: 16). In addition, also on May 20, 2012, a new location was discovered when a Hessel's Hairstreak was photographed in a cedar swamp in Winchendon by C. Kamp; this sighting has been accepted by the NHESP.

In 2013 at least one and probably two Hessel's Hairstreaks were photographed by multiple observers at Ponkapoag Bog on 5/19 through 5/21, and one or possibly two individuals were found in Acushnet Cedar Swamp in New Bedford (5/17/2013, M. Mello).

A recent analysis of MBC records using the list-length method indicated a small population decline for this species over these years, but the decline was not significant and included a wide margin of error (Breed et al. 2012). More systematic monitoring of a known colony, such as that at Ponkapoag Bog, using transect methodology, would get a more reliable assessment of population size and flight times.

State Distribution and Locations

The NHESP Hesselís Fact Sheet (June 2007) has the most comprehensive map of confirmed reports of Hesselís Hairstreak. Between the first confirmed discovery in Massachusetts in 1980, through 2007, Hesselís Hairstreak has been authoritatively reported from 21 towns according to the NHESP map; these towns are Abington, Auburn, Canton, Carver, Dartmouth, Dighton, Douglas, Dover, Foxboro, Holliston, Kingston, Lakeville, North Andover, Plainville, Raynham, Sharon, Sturbridge, Uxbridge, Westborough, Westwood, and West Bridgewater.

Many of these reports are from the 1986-90 Atlas period, when a concerted effort was made to search many white cedar swamps. The Atlas reported Hesselís Hairstreak from 11 towns in the state. The list of locations is also the result of targeted surveys by Mark Mello in the early 1990's, under contract with NHESP. Naturalist Richard Forster has provided an interesting account of his 1996 discovery, and Dick Waltonís videotaping, of Hesselís Hairstreak in Holliston (Forster, Massachusetts Butterflies, No. 8, 1997).

In 2012, after a search of a white cedar swamp in Winchendon by Carl Kamp and Brandon Kibbe, and a photograph of the butterfly by Carl Kamp, that location was added to the NHESP list. In 2013, Hessel's Hairstreak was discovered in a wetlands restoration area in New Bedford's Acushnet Cedar Swamp by M. Mello (5/17/2013 and 5/27/2013). Between 1980 and 2013, therefore, Hessel's has been reported from a total of 23 towns, but whether it is still present at many of the 1980's and 1990's locations is uncertain.

Hesselís Hairstreak is concentrated mainly in the southeastern part of Massachusetts ---on this, all three data sets, NHESP, the Atlas, and BOM-MBC ---agree. Nearly all locations for this species are either in south-central Worcester County or in Norfolk, Bristol and Plymouth counties. There are no reports from Cape Cod (Barnstable Co.), even though a few coastal Atlantic white cedar swamps do occur there. There are no reports from Marthaís Vineyard or Nantucket.

Notable finds outside of southeastern Massachusetts are North Andover (Essex County) (Atlas), and Winchendon (northern Worcester County) (Kamp/NHESP). To the west, the furthest west town in the NHESP database is Sturbridge in Worcester County. Auburn and Westborough in Worcester County also push the northern and western envelope. There are no confirmed reports from any part of the Connecticut River valley, or from Berkshire, Franklin, Hampshire or Hampden Counties.

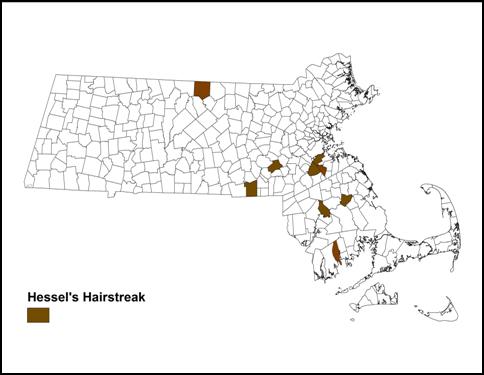

Sightings and photographs by MBC members are from a more limited set of locations. For the period 1992-2013 BOM-MBC records show only seven locations in nine towns (Map 31). These are Canton/Milton/Randolph (Ponkapoag Bog), Halifax, Holliston, New Bedford (Acushnet Cedar Swamp), Raynham, Uxbridge and Winchendon.

Map 31: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1992-2013

MBC trips have concentrated on Ponkapoag Bog, in Canton/Randolph/Milton, as the most reliable and accessible location for Hesselís Hairstreak (see 2007 photo above). As a result, the MBC high count for this species, 12 counted on 5/26/2007 by T. Gagnon et al., was at this location. Hesselís Hairstreak is usually found only as one or a few individuals.

Broods and Flight Period

Hesselís Hairstreak flies from mid-May to mid-June according to MBC records (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp ) Peak flight is usually in late May (NHESP 2007).

Earliest Sightings: In 22 years of BOM-MBC records (1992-2013), the earliest "first sighting" dates are 5/15/1999 and 5/15/2000, both at Canton Ponkapoag Bog, T. and C. Dodd. This is one day earlier than the Atlas period early date. Recent "first sighting" dates have been 5/17/2013 New Bedford Acushnet Cedar Swamp, M. Mello; and 5/20/2012 Canton Ponkapoag Bog, M. Rainey.

Latest Sightings: In same 22 years of BOM-MBC records, the latest sighting date is 6/15/1997, Uxbridge West Hill Dam, T. and C. Dodd. This is a few days later than the Atlas period late date of 6/11/1988, North Andover, S. Goldstein.

This species obviously has a very short flight time here. There is no evidence yet that it has a second flight period in Massachusetts, although it is known to have a partial second brood in July and August further south, and even three broods in Florida. In one coastal swamp in Connecticut, Hesselís Hairstreak has a small second flight of adults every year (Maier et al., 2011). There have also been two midsummer reports from Rhode Island (Forster 1997). In areas where there are two broods, the second flight of Hesselís occurs at approximately and same time as that of Juniper Hairstreak.

Outlook

Hesselís Hairstreak is distributed in scattered colonies along the Atlantic coastal plain from southern Maine to Florida and Alabama. Range-wide, it appears to be losing habitat (NatureServe 2012; Schweitzer et al. 2011). The greatest density of colonies is in southern New Jersey, southeastern Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. Thus, these states have a special responsibility to conserve and protect habitat for this delicate species.

The future of Hesselís Hairstreak in Massachusetts is tied to the fate of Atlantic white cedar swamps. Loss of this unique habitat has been substantial over the years in all states along the eastern seacoast, and while a good amount of quality habitat remains in Massachusetts, its conservation and restoration should be a high priority from a regional perspective.

Climate change could have an adverse impact on Hessel's Hairstreak habitat through sea level rise and increased hurricane-related tree blowdowns. In New Jersey, salt water rise has killed off many white cedars, and in Virginia hurricanes have destroyed many trees (NatureServe 2010). But beyond these admittedly important factors, there are no other climate-related reasons to expect a decline in Hesselís Hairstreak here; it is not a northern-based species so warming winter and spring temperatures should not pose an adaptive problem. Hesselís Hairstreak is provisionally omitted from Table 6 which suggests those species likely to decline here.

Aside from habitat loss through development, which may be prevented by existing state wetland protection laws, NHESP (2007) lists the following additional threats faced by Hessel's Hairstreak in the state today: suppression of fire and periodic flooding, and excessive deer browse, all of which can prevent the regeneration of Atlantic white cedar; hydrologic alteration; exotic plant invasions; introduced generalist parasitoids; and insecticide spraying.

© Sharon Stichter 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 6-28-2014

Species of Conservation Concern

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS