ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

52 Compton Tortoiseshell Nymphalis vau-album (Denis & Schiffermüller, 1775)

This handsome butterfly is uncommon in Massachusetts. Like the Milbert’s Tortoiseshell, it periodically expands into this state from the north, establishing temporary breeding populations. It appears to have been more common in the past.. It is probably declining today; hardly any were seen 2011-2014.

Our eastern North American sub-species of this holarctic butterfly is recognised as Nymphalis vau-album j-album. Nineteenth century entomologists like Scudder called it the White J Butterfly. Pelham (2008) uses the name Nymphalis l-album.

Thoreau found a Compton Tortoiseshell in Concord as early as 1858. Under some hemlocks along a brook he flushed a butterfly which was “tawny-orange, with black spots or eyes, and pale-brown about them, a white spot near the corner of each front wing, a dark line near the edge behind [trailing edge], a small sharp projecting angle to the hind wings, a green-yellow back to body” (Journals, Vol. 10: 341, April 1, 1858). Given the month and the nice description, Thoreau’s first editor, Bradford Torrey, was able to identify the butterfly as the “White J.”

Photo: Cummington, Mass., B. Spencer, March 10, 2006

Thaddus W. Harris had the earliest known New England specimens of Compton Tortoiseshell: he had two sent from Mr. Leonard in Dublin, N. H., who described the species as "very common in November 1826 and April 1827," and one dated October 10, 1836, Cambridge, which is probably the earliest Massachusetts specimen (Harris Collection and Index, MCZ). Scudder termed Compton Tortoiseshell “more properly a member of the Canadian than of the Alleghenian fauna...,” abundant in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, but very rare in the southern portions of New England, being seen only occasionally around Boston (1889: 383-4).

Scudder and Harris both noted the Compton Tortoiseshell’s intermittent appearance in southern New England: “This is another of the butterflies of which we see vastly more in one year than in another. Harris noticed this as long ago as 1827, as appears from his note books, but it is never very common in the southern half of New England, where most of our entomologists live, and no years can be specified (Scudder 1899: 384).” By the late 20th century, with more observers in the field, sightings were not intermittent, but actually fairly regular through the 1980's and 1990's, to 2010.

Collectors in the 19th and early 20th centuries were enamoured of this large, colorful and unpredictable species, and the resulting numbers of museum specimens may give a misleading impression of its actual abundance during those years. Prior to 1900, there were specimens taken in Massachusetts at Cambridge (1864, P. Uhler); Wollaston (1878, F. H. Sprague); Lowell (1891, W. P. Atwood); Braintree (1895, F. H. Sprague); Dedham (1896, C. Bullard), and Wellesley (1899, presumably Dentons). For the first half of the 20th century, there are specimens from Medford (1904), Princeton (1908, L. W. Swett), Tyngsboro (1914, 1916, H. C. Fall); Boston (1915); Milton Blue Hill (1916, P. S. Remington); Weston (1918, 1919, J. B. Paine); Sudbury (1922, O. Bryant); and West Newbury Artichoke Res. 1950 (Harvard MCZ, Boston University, Wellesley Insect Collection, and Yale Peabody Museum). Farquhar (1934) adds known eastern Massachusetts specimens from Sherborn, Sudbury, Marblehead (F. H. Walker), and North Andover (J. H. Treat).

Compton Tortoiseshell was known, but rather infrequent, on Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket prior to 1950. Several Vineyard specimens by F. M. Jones are in the Yale and Boston University collections: August 1931 (2), September 1945, and August 1949 (2). Other records on the Vineyard are from Gay Head July 1931, and Vinyard Haven September 1939. On Nantucket there are reports from 1912, 1936, 1937 and 1938 (Jones and Kimball 1943). Scudder records a major flight of “hundreds” into a lighthouse on Nantucket in September 1874. All reports from these islands are from late summer. They are probably not breeding and over-wintering individuals, but part of the occasional southward coastal movements of this mobile species.

Compton Tortoiseshell was first documented in central and western Massachusetts in the late twentieth century. It was undoubtedly there earlier, but there were few early collectors in those areas. Scudder mentions a 19th century outbreak in Springfield, and Farquhar (1934) refers to a Forbes specimen from Princeton. For Berkshire County, there is a specimen from Lee (1936, C. L. Remington) and several from Mount Greylock (1954, no. coll.) In 1967 R. Willis Flowers of Pittsfield collected the species in July at Pleasant Valley Sanctuary in Lenox, and in 1974 P. Carey collected it in June at Fannie Stebbins Refuge in Longmeadow (LSSS 1958-80). Near Sturbridge in 1978 there may have been a local outbreak, since D. Bowers found one in April "hibernating in a garage," and in September L. F. Gall and D. F. Schweitzer collected three specimens in Sturbridge, and W. Winter one. In Heath (Franklin Co.) S. D. Coe collected a specimen in July 1981; and in Sheffield D. S. Dodge collected five specimens in July 1982. (All specimens in Harvard MCZ or Yale Peabody Museum.)

During the 1986-90 MAS Atlas, Compton Tortoiseshell was found every year of the project, and was “relatively common," particularly in central and western Massachusetts and Essex County. Chris Leahy, author of the Atlas account, noted that the species had been “more persistent and widespread in southern New England since the 1970’s than previously.”

Host Plants and Habitat

Compton Tortoiseshell’s habitat is edges and openings in moist deciduous and mixed coniferous forests. Its numbers in Massachusetts probably declined during the period of forest loss 1600-1850 (Table 1). With the re-growth of forests after 1860, some habitat was re-established.

Host plants for Compton Tortoiseshell are trees: willow (Salix spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and poplar (Populus spp.). The eggs are laid in clusters on the leaves, and larvae feed in groups on the leaves, in a silken web. Our North American j-album sub-species of Compton Tortoiseshell is not known to be among the “Switchers” (Table 3); as far as is known it still uses only native tree species.

Adults overwinter in tree cavities, under eaves, and even in garages, outhouses and cottages (see photo above). Scudder (1899: 385) gives several examples of hibernation in schoolhouses and attics. In Massachusetts MBC records, there are reports of Comptons found overwintering in rural mail boxes and in sheds. So common is this use of man-made structures in rural areas that one might even call them a positive addition to the species’ natural habitat.

For nourishment, adults imbibe minerals from wet spots in soil (they are often seen on dirt roads through forests), and from tree sap, dung, and rotten fruit. Moth collectors sometimes trap Compton Tortoiseshells at sugar bait.

Today, Compton Tortoiseshell’s habitat and host trees are common in Massachusetts, and the species’ irregular occurrence and lack of abundance are more likely due to climate limitations.

Relative Abundance Today

Compton Tortoiseshell was reported as “locally common” during the 1986-90 Atlas years, but subsequently it has become less common. MBC records 2000-2007 rank it as an “Uncommon” butterfly during these years (Table 5). It was about on a par with Aphrodite Fritillary and Bronze Copper in terms of abundance.

Chris Leahy wrote in the MAS Atlas account that Compton Tortoiseshell in Massachusetts “periodically establishes temporary breeding populations,” which “may persist for a decade or more, following which the species may be absent for many years.” This dynamic probably describes many local populations in the state, for example the one found between 1997 and 2000 at Ipswich River WS in Topsfield in northeastern Massachusetts, which then apparently died out. In the state as a whole, Compton Tortoiseshell was never completely absent in any year between 1992-2012, but after 2010 only 1-2 individuals were reported each year, and none in 2013 and 2014 (Chart 52 and later records).

An important list-length analysis of 1992-2010 MBC data found a statistically significant 49.3% decline in detection probability of Compton Tortoiseshell over this period (Breed et al. 2012). Chart 52 also shows this decline. In addition, calculations published in the Massachusetts Butterflies season summaries show that the average number seen on a trip was down 68% in 2008, 49% in 2009, and 66% in 2010, compared to the average for preceding years back to 1994. The number of reports was also down in all three years compared to preceding years (Nielsen 2009, 2010, 2011).

Chart 52: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

Chart 52 shows two periods when Compton Tortoiseshell expanded into Massachusetts and undoubtedly reproduced here: 1996-8, and 2005-6. The 1996-8 expansion followed a large 1995 fall coastal flight in which individuals turned up as far south as New Jersey and North Carolina (Cech and Tudor 2005). The species is most migratory during years of population abundance in the north (Shapiro 1966; Scudder 1899: 385).

In most non-peak years shown on the chart, the numbers seen around the state were in the teens--- 17 in 1994, 14 in 2003, and 15 in 2008, for example. In the following years 19 were seen in 2009, and 14 in 2010, but then a drop-off began: only 3 were seen in 2011, 3 in 2012, and none in 2013 or 2014.

The chart fluctuations strongly reflect the fortunes of one well-monitored colony in Topsfield (Essex County) in northeastern Massachusetts. Compton Tortoiseshell was first reported at MAS Ipswich River WS in Topsfield in 1997, when Fred Goodwin, a staff member, reported seeing 23 on March 30. This colony was well reported in double digits in 1998, 1999, and 2000, after which no Compton’s could be found, until another good flight was noticed in 2004, 2005 and 2006. Since then, this species has not been reported from this sanctuary, and this once-flourishing colony appears gone.

Usually the largest number of reports and individuals has been in the spring (March and April), but these individuals could be either immigrants from further north which arrived the previous fall, or more likely local emergences from the preceding July (see life history below). Compton Tortoiseshell’s presence at some locations in north central and western Massachusetts has most likely been regular and ongoing, involving local reproduction.

State Distribution and Locations

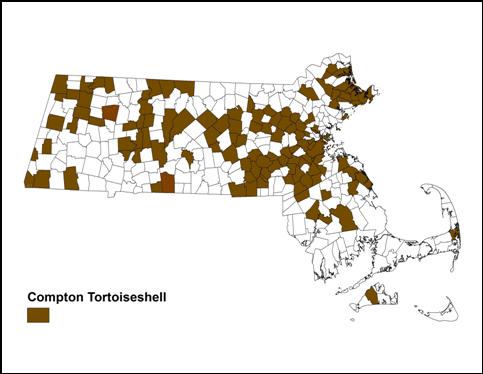

Compton Tortoiseshell is rarely seen in southeastern Massachusetts, but otherwise has been well-distributed across the state (Map 52). It has been reported from 116 out of 351 towns through 2013. The Atlas had found Compton Tortoiseshell “generally rarer along the coast,” but MBC records for the subsequent 20-year period show sightings in many northern coastal towns, including Nahant, Gloucester, Newbury, Topsfield and Ipswich.

Map 52: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1992-2013

In both Atlas and MBC data, spanning the years 1985-2010, sightings of Compton Tortoiseshell were much rarer in southeastern Massachusetts than in other areas of the state. The Atlas did not find this species at all on Cape Cod or either of the islands. In MBC records there is at least one report from Martha’s Vineyard (9/7/1998, M. Pelikan), and one from Orleans on the Cape (8/27/2008, W. Petersen). Mello and Hansen (2004) do not list Compton Tortoiseshell as regularly occurring on Cape Cod. MBC reports from inland southeastern Massachusetts (Plymouth and Bristol Counties), are shown on the map, but are usually of singles and are sometimes by less seasoned observers and could be misidentifications.

The Vineyard Checklist (Pelikan 2002) ranks Compton Tortoiseshell as Rare, with no spring records. The 1985-90 Atlas did not find it on the Vineyard; there are a few historical records from the 1930’s, and only one or two MBC records. On Nantucket, contemporary observers rank Compton Tortoiseshell as a “possible”, in view of the historical records from the 1930’s, but there have been no recent sightings and the Atlas did not find it there (LoPresti 2011).

Compton Tortoiseshell is usually seen in low numbers or as singles. The all-time state high number reported at one location is Scudder’s report of "hundreds" flying by Sankaty Head lighthouse on Nantucket on the evening of 11 September 1874. “One of the keepers brought me a dozen of them alive, saying that hundreds had flown into the lantern and there were many more outside (1899: 386).” A similar flight has not occurred since.

Compton Tortoiseshells could turn up in any wooded environment in the state, though they are less likely in southeastern and south-central Massachusetts. Some locations with multiple reports or individuals are

Boxford 10 on 3/28/1998, J. Berry; Dover Noanet Woodlands TTOR, 4 on 3/31/2007, E. Nielsen; Easthampton Mt. Tom SR 15 on 3/28/1998 , T. Gagnon; Harvard Oxbow NWR, 3 on 4/22/2007, A. Birch; Hingham Wompatuck SP, 8 on 3/15/2002, D. Peacock; Hopedale 8 on 3/30/1997, T. and C. Dodd; Natick Mumford Forest, 5 on 3/20/2010, B. Bowker; New Ashford Mt. Greylock, 12 on 7/10/2005 T. Gagnon, S. Cloutier et al., and 5 on 6/4/2010, T. Fiore; Stow Assabet River NWR, 2 on 4/22/2007, J. Forbes; Topsfield Ipswich River WS, 23 on 3/30/1997, recent max 6 on 4/10/2005, F. Goodwin.

Most of the larger counts have occurred in spring. In recent years, 2011 through 2014, there have been no large aggregations reported. On the July NABA Counts, numbers reported each year have hardly ever exceeded 5, even in the Berkshires, except that on 7/9/2006 (an outbreak year, Chart 52), 43 were reported on the Northern Berkshire Count, including 29 from Mt. Greylock.

Broods and Flight Time

Compton Tortoiseshell has an interesting phenology, similar to that of the Mourning Cloak and Eastern Comma. Overwintering adults emerge in early spring to mate and lay eggs on newly emerging leaves. The next generation of adults flies in early July, then aestivates until fall, when it flies again in October and November, before overwintering. The pattern seen in the MBC flight chart reflects this seasonal rhythm: http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp . Compton Tortoiseshells are seen most frequently in March and April, then again in July, with another small increase in sightings in mid-October. The spring sightings are presumably individuals which over-wintered in Massachusetts, but could be either locals or migrants which arrived the previous fall. The summer and fall sightings can similarly represent both local adults which emerged here as well as immigrant adults from the species’ permanent range further north. (They can migrate south in either spring or fall.)

Earliest sightings: In the 22 years from 1992 through 2013, the five earliest spring "first sightings" were 3/8/2000, Topsfield IRWS, F. Goodwin; 3/10/2006 Cummington, B. Spencer; 3/13/1996 Bedford, R. Forster; 3/14/2009 Andover, Ward Res. TTOR, H. Hoople; and 3/15/2002 Hingham Wompatuck SP, D. Peacock. The Atlas early date was 3/16/1989, Rehoboth K. Anderson. The spring flight dates seem not to have changed much from a century ago, when Scudder reported that overwintering adults appeared “occassionally by the middle of March (1899: 385).”

Latest sightings: In the same 22-year period the five latest "last sightings" were 12/26/1995, Princeton Wachusett Meadow WS, T. Dodd; 11/23/2012 Boxford, M. Arey; 11/7/2004 Cummington, B. Spencer; 11/5/2005 Cummington, B. Spencer; 10/30/1996 Walpole, D. Lang. The Atlas late date had been 11/6/1988 Sterling, S. Selkow. Scudder’s nineteenth century dates were similar: they continued on the wing “through October and sometimes even into November (1899: 385).”

Outlook

Cech calls Compton Tortoiseshell a “fairly adaptable” species, and certainly it is mobile and migratory. Still, it is not normally found south of New Jersey and Pennsylvania (see maps in Cech and Tudor 2005; Opler and Krizek 1984). It is only “occasional” in northern West Virginia (Allen 1997), and a "rare, irregular immigrant" in Ohio (Iftner et al. 1992).

The trend toward decline in this species in Massachusetts over the past 20 years has been detailed above.

The chief threat to Compton Tortoiseshell in Massachusetts is warming climate, since temperature apparently restricts its ability to reproduce successfully. More research is needed to determine the species’ climate tolerances and responses. Compton Tortoiseshell is listed on Table 6 as among those species likely to decline in Massachusetts if climate warms significantly.

© Sharon Stichter 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 9-25-2014

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS